In Timor-Leste, I meet a man who foretold the future.

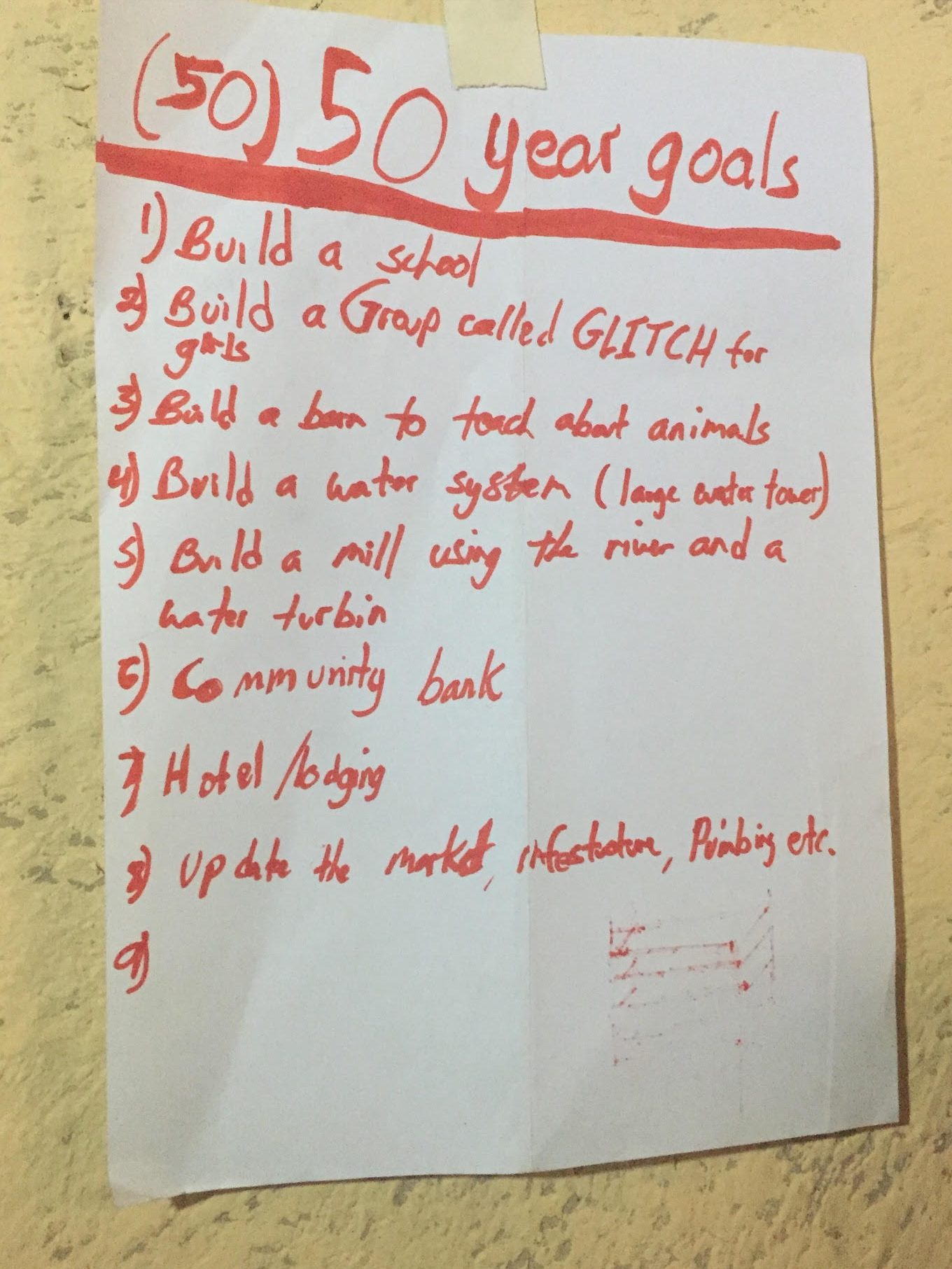

“Build a school.

Adam, Alieu, Timor Leste, 2017

Build a Group called GLITCH [Girls Living In The Community Happily] for girls.

Build a barn to teach about animals.

Build a water system [large water tower].

Build a mill using the river and water turbin (sic).

[Establish a] Community bank.

[Develop] Hotel/lodging [accommodations].

Update the market, infrastructure, Plumbing etc.”

Traveling to Timor-Leste on Peace Corps business in the spring of 2017, I am driven in a Land Cruiser by Daniel Mandell, director of management and operations of Díli post, four hours into the mountains over bad and barely-existing roads to the remote village of Alieu1. There, I meet Adam, a twenty-something community development volunteer who teaches English to Portuguese- and Tetum-speaking middle-schoolers and partners with the local priest to develop economic opportunities for subsistence-farming women and men in the village and surrounding countryside2.

After strolling past the tiny kiosks lining a 50-meter stretch of dirt he called the town market, Adam leads me to his construction site, where I meet a dozen men hammering siding onto a wooden frame in whose center scrapes a 300-lb hog tethered to a metal spike driven into the not-yet paved-over dirt floor.

“I raised ten thousand dollars in a Kickstarter back home. We’re building a training restaurant where some of the women you met in the market can learn a trade and something close to a living wage.”

“All these men work for you? Do you have a construction background?”

“Finance major in college. I just picked it up.”

I should mention that Peace Corps doesn’t proscribe volunteer projects. Its triple is to spread world peace through service, reflect the values of the United States, and develop servant leaders for life. The rest—what the boots do once they hit the ground—is up to volunteers like Adam.

Outside the planned eating establishment lies a 60-square-meter fish hatchery.

On a tour of Adam’s host family’s dirt-floor residence, I am shown the dining room where Adam and his “host father” traditionally seat themselves at the head of an empty table the remainder of the family will later occupy once Dad and Adam have dined and gone on their way. The “kitchen” consists of an electric hotplate, a plastic bin for carried water, some metal flatware, and one or two pots and pans. Later that day, I will meet Hanna, whose host family of seven initially crammed themselves into one of the two-room huts so that she could have her own “apartment” by dint of her paying them the American equivalent of fifty dollars in monthly rent. After initial resistance from her host parents, Hanna has managed to win over the girls who now dare to sleep on her floor. In Alieu, Adam has a room to himself in a luxury home by Hanna’s standards, whose host mother cooks in a “kitchen” consisting of an open firepit dug into the floor.

When Adam gives me a peek through some fabric hanging off the kitchen, I spy a posted sign on his bedroom wall, which immediately captures my imagination—and still holds it six years later. Mounted by masking tape to the yellow vinyl wall is the boldest example of city planning I have ever come across2. Scrawled unevenly in red MAGIC MARKER® across the top of what to me could have passed as Alieu’s Magna Carta are the words “(50) 50 year goals.” Take a look. And then ask yourself, Who empowered this young man to dare write such a manifesto?

Sure, the 50-count list is only up to eight by the time I photograph it. And Adam’s two-year Peace Corps tour would be cut short by COVID in less than a year. But that doesn’t faze him. He has already obtained a sworn commitment from the priest to finish what he’d started.

For the umpteenth time, I return to Hippocrates.

“Declare the past. Diagnoses the present. Foretell the future. Practice these acts.”

In my brief time at Alieu, I never learned specifically what the locals thought about Adam’s grand plans for their future. We stopped by the church but learned the priest was up-mountain ministering to a member of his flock. But in every other face I saw that day, the villagers’ love for Adam, his devotion to them, the care he takes for them, and his most rare vision for their impoverished lives4, told me all I needed to know.

The next day I learned in real terms of an equivalent scorecard I later retrofitted to Adam. Daniel has driven me and my American traveling companions, Mike Terry and Guy Draguelis, who had stayed in Díli when I was on the mountain with Adam, to see to some training for Rogierio Caetano, the post IT specialist, to the coast where we meet Thomas, another Peace Corps volunteer. In that conversation, I tell Thomas about Adams’s request that I line up some kind of app to help improve his English teaching. Thomas immediately begins rifling through his backpack for an ESL guide he has written and self-published—in the Tetum language and two local dialects—and exclaims while pulling out the rabbit, “No app required!” As part of a social enterprise Thomas has launched with a local NGO, the ESL manual is now featured in a bookstore in Díli whose shop owner told me is selling quite well: Well enough, according to Thomas, that a copier and supplies to self-publish a second edition have already been purchased from its proceeds. So solicitous has he become of the needs of those he is serving that Thomas’ village elders have offered to give him a plot of land, arrange a marriage, even name a mountain after him as enticements to stay in Timore-Leste beyond his three-year Peace Corps tour.

It is by the name-a-mountain reaction to Thomas’s service and the look in the eyes of Adam’s charges in Alieu, that I now measure anyone who dares to dream big and then follow up by serving bigger.

***

NOTES:

- Timor-Leste, or East Timor, is a Southeast Asian nation situated about 450 miles by air northwest of Darwin, Australia. The country occupies the eastern half of the island of Timor, whose west half is part of Indonesia.

- Timor-Leste struggled for independence from Portugal in 1975 and then Indonesia in 2002. Apart from its many local dialects, its official languages are Portuguese and Tetum.

- Employed once as a printer by my architect-and-city-planner father, I had seen more than my share of detailed city plans.

- While in Díli, I asked Daniel if the hundreds of young adults I saw on motorbikes were typical for the entire island. His explanation included a summary of the 1999-2002 Timor-Lest struggle for independence that stripped an entire generation of men from their families. “The majority of males in Timor today are under 24.”