Or How Orson Scott Card Taught Me to Understand Shakespeare Without Uttering a Word

Time it was and what a time it was

Paul Simon, Bookends

It was a time of innocence…

Preserve your memories

They’re all that’s left you

“I laughed so hard I fell out of my chair!”

Raise your hand if you’ve ever said those words. (Write back if you’ve actually performed them!)

The following story really happened.

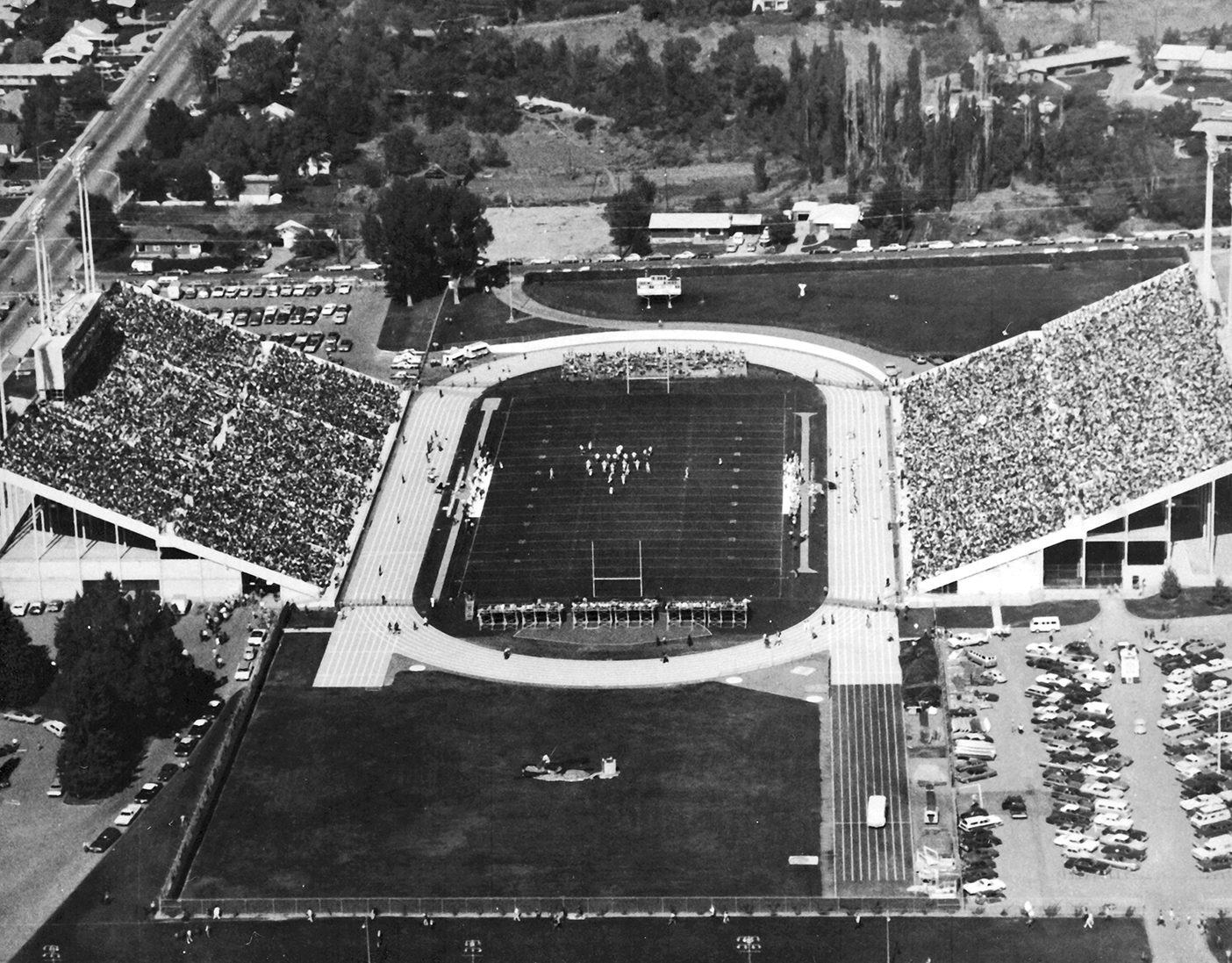

I have spoken liberally in these assays of bias about the connection between the ancient words theory and theatre.1 It comes down to judgments we make about the world from the place we sit at the time we make them. In Time’s Gravity, I write about seeing a different Hamlet than the one my sister experienced the same night in the same theater, but while sitting in a very different seat. In high school, while performing in Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing, some of us began to wonder aloud at the bellowing laugh coming from an unknown patron sitting on the extreme stage right edge of row four of the amphitheater.

“Who is that guy, and why does he keep laughing in all the wrong spots?” This was Anne Ashworth, a friend of mine to this day.

“I think he knows something we don’t. This play might be funnier than we thought.” This was Kim Golightly, also a good friend. “I think I’ll ask around.”

Years later, Anne and Kim, happily married, invited Kari and me to a performance of the same play at the Foulger Theater in downtown DC. Watching Kelly McGillis and David Selby as Beatrice and Benedick brought back fond memories, including a bizarre one I still ponder.

“Remember that guy who couldn’t stop laughing when we did this show in high school?” Anne again. “Did we ever find out who he was?”

“It was Orson Scott Card,” remembered Kim. “We met him in the green room the next night.”

“I think he fell out of his chair,” said no one in particular.

“It was the amphitheater desks,” I chimed in. “It’s where Kari and I met and fell in love during theatre class the year before. We came up with this mime of two people getting married…”

[“Don’t go there, Scott,” I can hear Kari’s foot threatening me under the table. Guess I won’t.]

The desks were these steel folding chairs with the flip-up armrest that hooked around to form a small desktop. And if you leaned too far back in them, your behind would begin to slide forward.

“I remember them,” said Kim. “And if you slumped in them, you’d have to grab the armrest to keep from sliding out. We’re backstage trying to figure out where all the laughter is coming from, and here’s this guy clinging to the armrest, laughing so hard he starts to lose his grip!”

“I remember now,” adds Anne. “He was funnier than I’m sure our high school performance was.”

***

In my early career, I made a living watching people. As a knowledge engineer, I was often hired out “to box up people’s brains” for transfer into a computer. I would ask my subjects question after question and then plot each answer on a whiteboard grid called a decision tree. I then coded the set of decisions into software, so far less experienced trainees could benefit from having a virtual expert to hand whenever they got in over their heads.

Over time, I boxed up some fascinating brains. There was an oil exploration guru at Exxon whose formula for striking “bubblin’ crude. Oil, that is: black gold; Texas tea” (I’ve always wanted to write that!).2 His expertise seemed to me more art—magic even—than science.

I interviewed for hours a telephone agent at a credit card company to capture why her customer service cases closed twice as quickly as her peers.

“If all our agents were as intuitive as Colleen, we could get rid of half of them.”

(I’m pretty sure the non-disclosure agreement I signed with that bank has long since lapsed.)

As I wrote in Once a Mouse…, I once attempted to sleuth from executives at Universal Studios their most profitable combinations of actors, directors, and marketing campaigns to tease out patterns they could replicate when making future motion pictures. The limitation of AI in those days was that if a human being didn’t know the way something worked, there was no way a computer could figure it out. Not so today. Feed an AI the raw data, push a button, and out pops genius investment decisions. Or so goes the sales pitch.

I’ve been selected for jury duty.

Steven Wright

It’s kind of an insane case.

Six thousand ants dressed up as rice and robbed a Chinese restaurant.

When challenged by Marriott to find a better way to clean hotel rooms and things, I spent a lot of time with early robotics pioneer Joseph Engleberger. After building the first robotic arm, Joe moved on to service robots and was already working with Electrolux of Sweden to design self-guiding vacuums to clean ballrooms, guestrooms, hotel hallways, and the corridors of hospitals and office buildings.

“Ever notice the quirky path of an ant walking across a tabletop?” he once asked. “Ants don’t walk straight; they jig and jag like they’re lost. Only they’re not.”

This was vintage Joe, always holding court on the way he came at an idea. He was cajoling Rich Shcroth, Anne Golightly—the very same—and me at a dinner with Electrolux executives in Stockholm.

“I studied insects for years. Unlike chickens whose eyes can see afar off—it’s how they know to get to the other side, right?—ants follow microscopic bread crumbs called pheromones laid down by their predecessors on the road to or from the nest. They can’t see ahead, so they bob back and forth like a white probing cane to stay close to the breadcrumbs.”

“Our first robots followed a magnetic cable we laid under the carpet. It’s how Pitney Bowes routed mail to office cubicles. But the cable kept breaking—it was always underfoot, and this heavy cart drove on it several times a day. And the cart couldn’t maneuver around obstacles, like obstinate employees.”

“So, I studied bees instead. Birds navigate thousand-mile migrations by sensing the earth’s magnetic field. But honeybees are too small to register that. So they dance.”

“They dance?”

“They do. When they’re out in search of pollen or checking their stashes of honey, they memorize landmarks—maybe how they smell, how long to fly between each, all the turns, that kind of thing. Back at the hive, they do this elaborate dance to pass along to their compadres directions to the clover field.”

***

And you know what they say…

Dale Wasserman, Man of La Mancha

“Whether the stone hits the pitcher

or the pitcher hits the stone

it’s going to be bad for the pitcher”

Connie O’ Massey was a civil engineer who designed the landing gear for the classic passenger jets—DC-8, 9, and 10. When he retired, because of the chasm of knowledge that separated Connie from the rest of the engineering team, Douglas Aircraft brought Connie back to allow me to put his abundant brain into a box. What struck me in my whiteboard sessions with Conne was how little landing gear design depended on the aircraft but on the runway.

A fully laden Boeing 747-800, still the largest commercial aircraft ever manufactured in the U.S., can weigh up to 987,000 lbs. That’s almost 500 tons or roughly the weight of 35 double-decker buses. But when that many “buses” hit a runway running, its downward force at impact, even at the meagerest angle, is equivalent to at least 350 buses. We’ve all seen sensational images of airplanes in crisis making emergency landings on freeways. But never a 747. The asphalt would immediately buckle. Or, as Don Quixote’s sidekick Sancho Ponza would say, “…it’s going to be bad for the pitcher.”

“You don’t drop a weight like that from a great height on just any hard surface,” Connie told me in our first session in a hangar-turned-cube farm in Long Beach, California. “It’s gotta go deep, and it’s gotta be reinforced like no other. In some of the older airports, you just can’t land it.”

“Because the runway’s not long enough?” It’s obvious to Connie I haven’t been paying attention.

“That’s an urban legend. Because the bulbous nose of the ’47 keeps it airworthy at a lower speed, it actually needs less runway. ‘If a 747 can’t land at your airport,’ I tell them, ‘it’s because it can’t land on a gravel road.'”

***

“I love to watch people,” he would tell her. “They come from all over, mostly Japan, but everywhere, really. I can watch them for hours, and if they’re up for it, ask them about their lives.

Joseph Engleberger observed insects to learn how to design robots. Connie O’ Massey measured the strength of roads to calibrate the wheels beneath the airplanes that landed on them. But when we people-watch from a distance, a kind of benevolent recursion jumps us toward what Gandhi might have called the change we wish to see in the change we wish to be.

Kari’s maternal grandfather Elwood Christensen taught her to be curious by the way he interacted with strangers. After his wife Arva died, Elwood’s evening routine consisted of driving to Waikiki, parking beneath Davey Jones Locker, and then walking out to the famous beach, where he swam every night for half an hour. Following his swim, he would sometimes walk out to Kalākaua Avenue, where he would hang for an hour or so. Kari, who swims like a fish, would sometimes accompany him. Before moving to the mainland and on annual trips to visit him afterward, she always enjoyed observing his joyful observations and is today the most curious friend I have.

“I love to watch people,” he would tell her. “They come from all over, mostly Japan, but everywhere, really. I can watch them for hours, and if they’re up for it, ask them about their lives. Where are they from? What are their plans? If they ask, I give them directions. If they seem the curious or adventuresome type, I’ll tell them about places far from Waikiki. I might send them to Haleiwa or Waimea, somewhere off the beaten path. But mainly, I just listen. I love learning about people.”

Did he actually hit the floor? As I look back, had he come completely unglued from his seat, the unwitting by-sitter in row three wouldn’t have had a prayer. The Amphitheater desks were not bolted down; it would have been quite the pile-up.

All of us watch people. When we do, we can’t help copy-pasting onto ourselves the best bits we spy on them. As children, we learn almost everything by emulating those around us. From my backstage perch with Anne and Kim that evening back in 1975, I’m studying the young man, not even a handful of years my senior, who will in ten years’ time become the author of Ender’s Game, a break-through novel addressing the moral boundary between simulation and emulation. As he watches Shakespeare’s original rom-com, whose combative lovers Beatrice and Benedick Jane Austen will emulate two centuries later3, my Don Pedro begins to emulate Card’s Jonathan Winters.

Act I: Don Pedro and other cast members recite Shakespeare on stage. Winters laughs. Don Pedro thinks, “Oh, I see. Shakespeare must have meant thus and such,” and makes a mental note to dig deeper into his lines.

In Act II, Don Pedro is coming up on a line whose rhetorical pattern calls to mind an earlier private gutbuster from Winters. But this time, Don Pedro adds a wry smile, punches its ending in a different direction than he’s rehearsed, and looks right at Winters, who laughs even bigger, but does so a split second before Don Pedro’s punchline.

“What is he trying to tell me? Maybe it’s this…”

(It’s been fifty years. Don’t ask me to remember what Winters was laughing at, at the time. It was all so new to me, anyway.)

In Act III, Don Pedro gathers what he has learned from Winters in Acts I and II and approaches Shakespeare’s humor freshly still.

[Insert here with knowing emphasis long ago forgotten line. Wink at Winters, who may be about to fall off his chair.]

But Winters doesn’t make a peep. Don Pedro has jumped the shark, tragically bounced, and is now in the roiling water without a paddle.

In Act IV, desperate to survive, Don Pedro grasps what he thinks to be a lifeline by coming back to something he said in Act I. He goes all in with the new subliminal message. Winters acknowledges it, but only tentatively, before absolutely roaring 30 seconds later. Don Pedro is hopelessly clueless but there’s always Act V.

By then, taking it all in and summing it all up, Don Pedro delivers his climactic line, and the payoff arrives right on cue. For his part, Winters has put it all together as well and is now guffawing so hard he first slips and then slides beneath the armrest desktop toward the row below him. Did he actually hit the floor? As I look back, had he come completely unglued from his seat, the unwitting by-sitter in row three wouldn’t have had a prayer. The Amphitheater desks were not bolted down; it would have been quite the pile-up. (I might have exaggerated the title of this post!)

That’s not how it happened, of course. Not in real-time, anyway. I have described the kind of benevolent progression that, in The Case of the Slowly Progressing Plodder That Used to Be and Undoubtedly Still Is My Own Brain, can sometimes take years to unfold. Card came to Much Ado in my senior year of high school. The following year I would enroll in his college playwriting course, writing my This to his That: read one; write one; rethink one together. The course, mercifully repeatable for credit, I then took again. Once in a blue moon, I have since written to him with this or that idea, and he has been gracious enough to write back. I sent him a draft of this post. No indication if he managed to remain seated. Regardless, he is one of the people I continue to watch.

- See my post, Schrödinger’s Cat Burglar, for how the words theory and theatre share the same Greek root. For this post, consider that If you’re sitting in the fourth center orchestra row in the theater—my preferred point of vantage—you will experience a very different theory of the show than if your back is leaning against the cold, damp cinder wall behind the last row of the upper balcony as mine was when looking down at Ralph Fiennes from a great height during his 1995 performance of Hamlet.

- See the opening credits of the 1960s television comedy The Beverly Hillbillies.

- Much Ado About Nothing is considered by many the “mother of all rom-com.” On Charles I’s private copy of the Second Folio, the king himself crossed out Shakespeare’s nominal title and scrawled “Beatrice and Benedick” below it, echoing the poignance of the duo’s hot-and-cold relationship and every romance that works its way from love to hate in a madhouse matter of hours. For more on this idea, see Ace Pilkington’s Much Ado and Pride and Prejudice: Twin Characters and Parallel Plots.