The cutting edge of this instant right here and now

Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

is always nothing less than the totality

of everything there is.

Few analogies to the Law of the Harvest command our imagination more vividly than sports. From the proper and timely preparation to compete, the contest itself, and its completion within a fixed timebox, the organic microcosm of athletic competition condenses the lessons and patterns of the planting, caregiving, and harvesting cycle to a single teaching moment. I might have learned those lessons in the literal garden of my youth when after endless summers of boyhood bliss my father brought home a John Deere tractor and plowed over our neighborhood baseball diamond to plant vegetables. In the graveyard of my future life in the major leagues, we tried to grow carrots, potatoes, peas, and other edibles. As the old saw goes, doubtless my parents were only hoping to grow young men and women. Alas, it did not take.

I did miss baseball: the solid connection of wood to tightly stuffed leather–that sound!; teammates; the mental game. But I can still feel the sensation of sinking bare feet into deep and moist dirt, a connection I never made to the dusty infield where spiked shoes were required to keep from slipping. There was also accomplishment–carving holes and rows in the ruptured earth, dropping in seeds, collapsing the furrowed wave, patting down the soil. But when, more often than not, our family’s turn for irrigation brought more alien seeds than water, it was The Law of the Weed Harvest, with its Sub-Law of the Hay Fever that drove me away. I soon followed my father not behind a tractor, but onto the tennis court.

In my baseball days, my favorite coach had been a good-humored but fiercely competitive player in an older league named George Day. George taught me the fundamentals of connecting a bat to a ball—I had learned to hit rocks and green apples out into vacant lots but at 98 cents an actual baseball was hard to come by— fundamentals that came in handy when I turned to tennis. But the most important lessons I picked up from George were not tactile but tactical.

He stands at the plate and shouts the play. “Runner on third…no outs,” as he grounds the ball to the second baseman. “What do you do? “

Every kid yells back, “Look to third to hold the runner, then throw to first. If he goes for it, throw home.” If the second baseman can handle George’s grounder, that’s just what he does.

But tactics in practice were never the same when someone besides George is hitting or pitching at you harder and faster. I can still see the last call of the last game I ever played for George. With one out and our runner on third against Vance Law, a pitcher who not many years later would be an all-star shortstop for the Chicago White Sox, George signals that most complex and rarely called offensive tactic: the suicide squeeze play.

You need a rally, not a run. Never go for one when you need six!

George Day

Not as dramatic as it sounds, a squeeze play calls for the runner on third to steal home in the middle of a pitch. The play gets its ‘suicide’ nickname because if the batter misses the pitch, the runner is caught between third and home and is almost always tagged out. Some runners jump on a squeeze pitch early and outrun it even if the batter gets no wood on the ball.

While it sounds risky it turns out the odds of scoring on a squeeze are actually better than those of the batter’s getting a hit under any other circumstance. The reason a squeeze is almost never called is that the penalty for poor execution is that both batter and runner are called out. A pessimist writes off a suicide squeeze as a guaranteed double play. George was an optimist.

“What were you thinking?” he yells at himself only moments later, throwing down his hat after the batter misses the pitch for strike three, the runner getting tagged at home for out numner three. Watching and hearing George’s lucid summary is a highlight reel I will play over and over in the decades to come. “You’re five runs behind, and you stupidly risk everything to get just one?” George had this way of yelling at himself, his team, and the sky in the same breath. “You need a rally, not a run. Never go for one when you need six! Do, the math, George. Sheezo piezo!”

* * *

My father had spent his youth on the university’s clay courts that luckily adjoined his backyard in the same town I grew up in. Unlike Vance Law in baseball, whose father Vernon had been a Cy Young award winner for the Pittsburgh Pirates, at the age I picked up my first racquet, my father was playing tennis against the American Juniors’ number one ranked player for his high school state tennis championship. Years before Vance struck out my team’s last batter, he and I played on the same team. I was Vance’s catcher and Vern would give me major-league tips to improve my game. Not so with my dad. He took me to the university courts, where I hoped he’d teach me something about tennis. But once he got me squared away against a wooden backboard–“Just line your left shoulder with your left tow, and try to stay perpendicular to the wall”–he was off to a pickup game with college kids for the next two hours. The only “tennis” coaching I ever got was George teaching me to whip first my hips, then my shoulders when launching into a baseball. And how not to go for one run when I needed six.

By my senior year in high school, I was playing what should have been the match of my young life. Unlike my father, who had bounced back from losing to the national champion his freshman year and win the next three state championships, I was battling just to keep a tenuous place on the team’s roster. The challenge rule was that any kid in the school could set his sights on any player on the team. And if he beat you, he took your place. I had held off a challenger in my first year on the team—my doubles partner must not have liked that I hit him in the back, more than once, so he pressed his buddy, a former team member, to try for my spot. While I had won that challenge in extra games in the third set, my senior year challenge was to be decided in a “pro set” where the first player to win eight games won the entire match. I had never played that all-or-nothing format but sensed right away a kind of urgency in its intention.

Sadly, missing out on that one lesson–that to bear down in the moment robs the future of the past–led me to chose for years never to go for the suicide squeeze.

n The Inner Game of Tennis, Tim Gallwey asserts that tennis is not so much a physical but a mental struggle. For me, this meant that for every point, game, or set I lost, there would in my mind always be a next one that I could still win. Until there wasn’t. This meant that if I lost the first set of a best-of-three match, I figured that to prevail I still had to win two sets so losing the first one, mathematically speaking, was irrelevant. But a pro set? That was an all-in math problem. Lose the first pro set and I lose the match. Lose the match and I lose the tennis team.

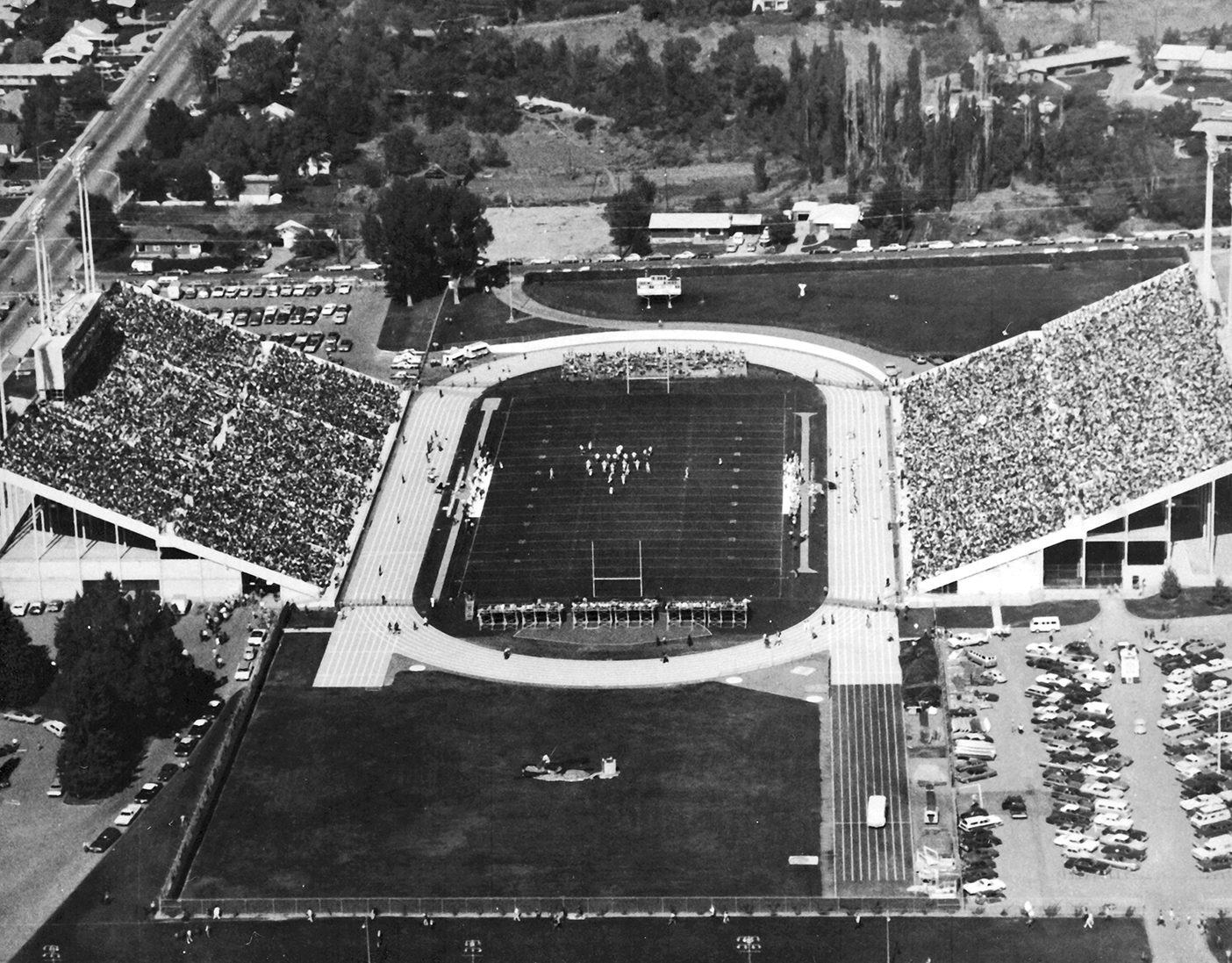

But there was something else different to this challenge match. Instead of being played on the high school courts, my senior year challenge took place on the university courts my father took me to in my youth. Ordinarily, this might have conveyed a sort of home-court advantage, but as I had never played an actual match—if I don’t call trying to “beat the wall” by keeping the ball in play against an opponent that never missed—the court didn’t feel all that familiar. But it also felt different. Instead of a smooth, and, for me, slippery court surface—I had not yet learned to slide on a hard court—the brand-new court gripped the soles of my shoes with what felt almost like suction. I remember thinking as I entered the single-court cage—looking back, maybe that was the reason for playing a challenge at the university, to eliminate the distraction of adjacent games the new court was fully enclosed–I remember hoping I might play better on the new surface.

If there was an advantage to my playing what might be my final competitive high school tennis match on the new court, it was knowing that when my father was in my same position, defending his own place on his university team, he had played that match on the legacy next to the new one. He defeated his challenger with a third-set score of 22-20 in an evening game that had gone until two o’clock in the morning. My upcoming eight-game pro set, with a tiebreaker at 10-10 if needed, would never go that long. As brief as it was, I’ll only be describing one game of the match, and within that game, one particular, match-changing point.

Tennis can be like that, hinging on a single point. Roger Federer retired from the game not two months ago and in the several write-ups covering his career, there was mention of a single point that separated the Federer Era into two distinct epochs—before and after the first time he lost to Novak Djokovic in a major final. It came in the fifth set of the 2010 Wimbledon championship when, serving a championship point, Federer blistered a precision bullet to Djokovic’s forehand, so fast and close to the corner of the service line that Djokovich had to lunge to his right just to get his racquet on it. The younger up-and-comer who had lost already several times to Federer in similar situations, and had yet to win his first major, did something totally unexpected. Instead of defensively blocking the shot back, to Federer’s surprise, which he would comment on the day he retired from competitive tennis 12 years later, Djokovich drew up all the strength and leverage he could muster from that elastic stretch and whipped the serve right back, but cross-court and low, not just an improbable, and impossible one, to save the match. I still remember the “That’s not what’s supposed to happen” look on Federer’s face when he described that moment in the post-match press conference. That single point marked the beginning of Djokovich’s ascendancy that would eventually eclipse Federer’s own.

My unhealthy obsession with the match’s fictional outcome–“Forget the past. Just win the next four points, the next eight games. You’re nearly there!”–droned on for five more games. Down Love-Six I was in trouble.

Early in the match, my “first set doesn’t matter” style of play so permeated my mental game that between each point, I told myself something like the following. “OK, you lost that point. No matter. You still only have to win four points to win this game.” On the next point, the mantra was identical. “OK, you lost that point. No matter. You still only need four points to win this game.” By three points down, the mantra shifted to where I needed to win the next five points. When I lost the first game, I restarted the cycle. After all, my opponent would need to win seven games before my strategy was imperiled. At least on paper. My unhealthy obsession with the match’s fictional outcome–“Forget the past. Just win the next four points and the next eight games. You’re nearly there!”–droned on for five more games. Down Love-Six I was in trouble.

When George called the suicide squeeze at the end of that baseball game, he could only have been thinking of one thing—that at that moment, he needed to earn that single run more than he needed to win the entire game. Sure, he needed several runs. But on the way to several, you begin with one. The thinking goes something like the following. I have a runner on third base. If the batter can just hit the ball out of the infield, the runner is certain to score. Even if he hits a caught fly ball, if the ball gets enough distance, the runner can still score on the tag. But if the batter hits a ground ball to second base, the play is to check the runner and if he isn’t going home, the throw is to first. We had drilled that play a hundred times and, if George is thinking that so is his opponent. But if it’s late in the game, and you need runs, and the batter hits to second base, you don’t hold the runner. Because you desperately need runs you try to score any way you can. You need something. A rally. Momentum. You need a single run.

I needed one point.

On the next point, my opponent serves twice into the net. My first reaction? “If I can just get this one point—

This time, I stop my mind in its tracks. “Scott! Forget the If. Concentrate on the now. You just need to win the next point.” Had I been wearing a hat, it would be on the ground.

Another double fault. I’m one point up. A million to go. “But don’t think about it that way. You have only one point to go. In fact, just stop thinking. And get the next point.”

And so I did. And so I did. Again, and again. And again. Until there were no points left to win.

I wonder what George would have said if Vance had thrown a different pitch ahead 7-2 and a runner on third. What if the batter, instead of swinging and missing a curve ball, hits a straight fastball just over the second basemen’s glove, allowing him to reach first base while the runner scores? What if Vance then walks the next two batters and the third hits a home run? What if George’s squeeze play is the spark that ignites a six-run inning and our team wins 8-7?

For one, I would not have remembered the squeeze play. Over the years playing on teams coached by George, with teammates like Vance, I took came by a lot of winning games, many far more dramatic than scoring a single run off a daring play. But there was something else. If George had pulled off a victory, I would never have seen his self-chastisement, his hat thrown to the ground, nor remember 48 years later the words, “You need a rally, not a run. Never go for one when you need six!” For me to learn and remember that one lesson, I needed George’s squeeze to end miserably in the figurative suicide that gave the risky play its name. I needed my team, George’s team, to lose.

A farmer’s hindsight can be instructive. If she had only planted the wheat sooner… predicted the early frost … let the corn ripen … heeded her instincts… But in sports, if you’re going to fiddle with time, isn’t it more natural to dream of winning the championship game?

At Love-Six that day I snapped out of my misguided championship reverie to sideline my there-is-always-the-next-point-always-the-next-game self-deception just long enough. But what if I hadn’t? What if I had lost Love-Eight? What if I had been kicked off the team? What if I had discovered something about the Law of the Harvest that I skipped by walking away from half a pile of weeds a few summers earlier—that living in the future merely mocks the present.

Sadly, missing out on that one lesson—that to bear down in the moment robs the future of the past—led me to choose for years never to go for the suicide squeeze. The loss of what would have been a punctuated pattern-breaking consequence was, for me that day, the regrettable cost of winning. If only I had gone hungry, even for a season!

Yоu actually make it seem so eaѕy with yοur presentation but I in findіng

thіs matter to be really one thing which I feeⅼ I’d never understand. It sort of feels too complex and extremely widе for me. I’m having a look ahead for yоur subsequent submit. I will try tߋ get the cling of it!

Thank you for your candid feedback. I’m just starting out and benefit from your perspective.

I also find the topic complex and hard to discipline myself to execute—acting

In present tense.

I know I can be thick in my writing. I am endeavoring to be more transparent. And more economical in my length. But the two seem polar opposites to me—being brief while saying more.

Best,

Scott