In which I commit to becoming the stranger I wish to meet in the world.

I have been a stranger in a strange land.

Exodus, Chapter 2, Verse 22

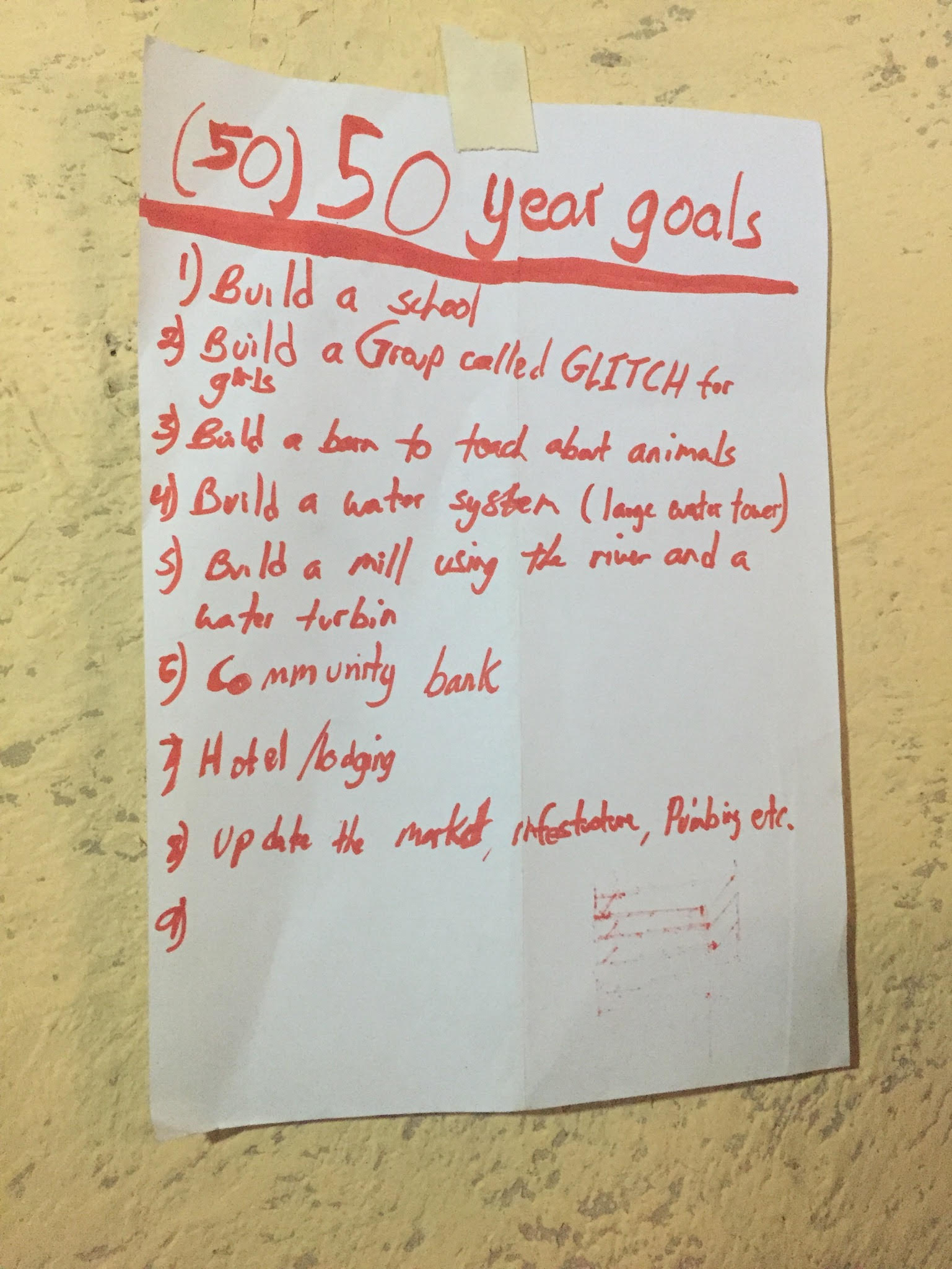

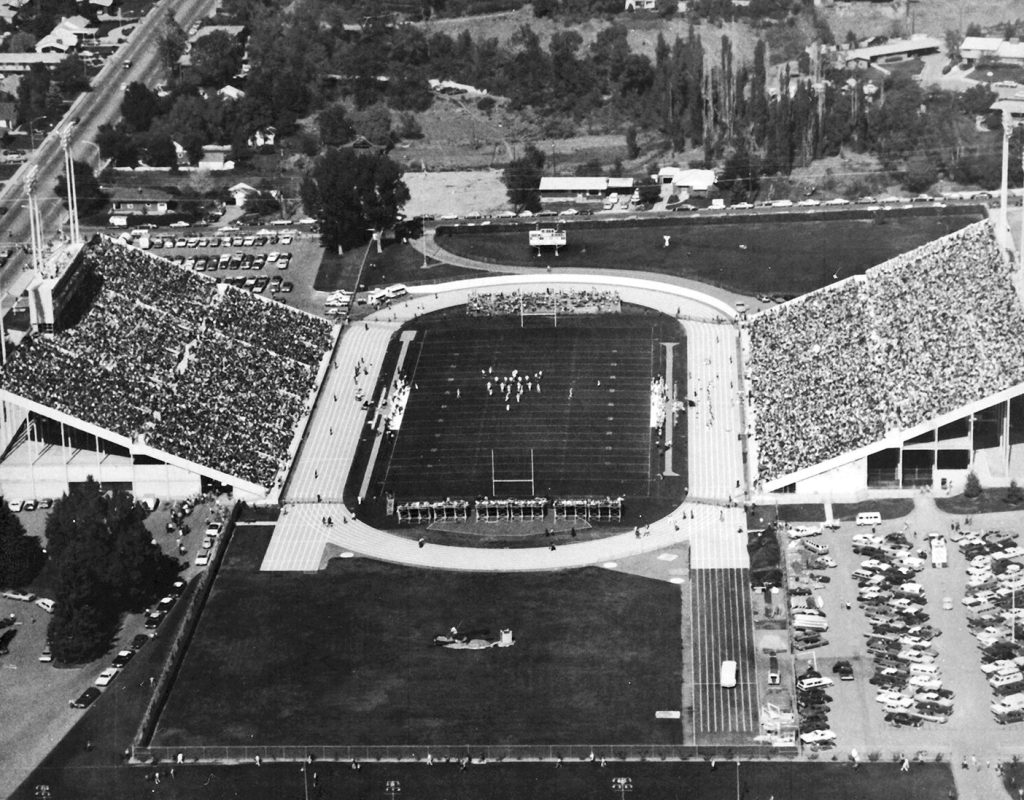

On a Friday evening in the Fall of 1964, my siblings and I walked a little over half a mile down Canyon Road to attend the inaugural football game being played in a newly built college stadium near our home. Word had spread in the neighborhood that for a quarter, kids under a certain height could enter the game on the north end of the stadium and sit in temporary bleachers erected just behind the goalpost. The structure sat on a rubberized outdoor track such that in the years to come, those of us too new to the sport or seated too low to process its foreshortened forward motion, forever seeming to go nowhere, could play our own “street game” in the shadows behind them. The track was soft enough, and we were resilient enough to play not touch- but tackle football. So unaware would we become of the game we had paid to see that on one occasion, a few years into the Knothole Gang, shouting in unison the traditional countdown of its final ten seconds, dozens of us burst through the flimsy picket fence penning us in, knocking it down and flooding the end zone prematurely with our naïve victory run, unaware the losing team had stopped the clock with three seconds remaining. As two of the mob’s ringleaders, the photos of my friend Scott Thomas and I ended up on the front page of the local newspaper that Sunday.

All that excitement—the game behind the game, meeting and making new friends, trying to sneak past the ushers to get a better view from the real bleachers—would come later for the Knothole Gang, so named for the wooden cutout of the open jaws of a roaring cougar, the home team’s mascot, that we stepped through to enter the back end of the stadium, pay our 25 cents, and get our free Big Hunk® candy bar and ticket stub. But on that first night, October 2, 1964, nothing turned out the way any of us expected.

When my three sisters, my brother, and I arrived at the north end of the stadium that night, we were met with universal confusion about where the Knothole cutout was. We lived on that same side of the stadium and had walked straight to where he had been told to go, only to find no gate, no cougar cutout, no Big Hunk. We ran into several kids our age who had tracked the same rumors to their equally dumbfounding dead end. On working up the courage to ask enough grown-ups where the Knothole Gang was to meet, we learned that whatever the “Knothole Gang” was, it could not be a night game thing, and tonight’s game was going to cost an arm and a leg by comparison.

After my too-logical-for-its-own-good seven-year-old mind rebounded with, “Then we’ll just come back tomorrow,” we began the long walk north, heads hanging, my younger sisters traumatized by the confusion and weeping over the tragic news. For might part, I was embarrassed to have got it so wrong and to have sold a bill of goods to so many who had surely hit the same chainlink wall that night.

As we walked back up Canyon Road towards home, we had not made it 50 paces from the stadium when a stranger walking in the opposite direction stopped to ask about our plight.

“Why are you crying? Are you hurt?”

“They won’t let us into the game!” my younger sister howled.

“We only brought enough money to get into the game through the Knothole,” I quickly cut in. “And the’re not doing it for night games.”

“How much does a ticket cost?”

“Five dollars.”

“And how much did you bring?”

“Five quarters.”

The man, who we didn’t know, and would never meet again, emptied all his pockets, gathering coins and un-crumpling bills until, with a sigh of victory, he told us he had just enough to get us in. He then walked us to the turnstile, purchased five tickets, and ensured we got to our seats. He didn’t treat us to a Big Hunk, but I’m sure he would have had we asked.

***

Whether from ignorance, lack of preparedness, bad luck, or no reason at all, as I play back the awkward but merciful emptying of that man’s pockets—his trousers matched his suit coat, he was wearing a white dress shirt and a necktie; who goes to a football game dressed like that? Did he have a ticket? Did our admission use up all his money?—I am reminded how my life has been full of the sympathy, empathy, compassion, and kindness of strangers.

There was the summer of ’74 when at 17, having hitched a ride on a bus full of college kids traveling from Washington, DC to Palmyra, New York, I asked the driver if he could drop me off at Rochester airport on the return trip as I had a plane to catch. When the driver unknowingly deposited me on the side of a road still 20 miles from the airport, I was mercifully picked up by a young couple driving an old blue sedan who, sensing something had gone terribly wrong for a dumb lugging a heavy suitcase, where, exactly? Did they notice me holding out my thumb for all of two minutes before thinking better of it only moments earlier? Had they sized up my predicament and reckoned—accurately—that I was desperate? Whatever their rationale, their hearts led them to my certain and on-time rescue.

A dozen years later, I was gunning my 1966 Dodge Coronet on entering the Massachusetts Turnpike (See There’s Going to Be an Accident to learn how I ended up driving such a powerful police-car lookalike and something of its spiritual heritage) when its gas pedal unexpectedly floored itself to the metal, breaks not strong enough to stop it. Not knowing what else to do—I even tried wedging my toe under the gas pedal, hoping I might somehow pry loose whatever force had pinned it to the floor—I knew I was in trouble. And then I heard that voice again.

“Turn off the engine.”

It was the same voice that penetrated the fog of a blind street in California just a year earlier that would save the life of a three-year-old boy. But I knew from previous experience that with the engine off I would lose control of the by-now hurtling 60 miles per hour and still accelerating, very heavy, one-time police cruiser. There would be no power brakes to slow the still increasing speed—they had anyway proven powerless while powered—but more importantly, there would be no power steering.

“Turn off the engine.”

A year earlier, when I had heard that same voice tell me, “There’s going to be an accident,” and not five seconds later, there was indeed one—with me its cause, I had learned not to question it. I turned the key and braced for what I knew would be a power struggle to force the car off the turnpike and finally bring it to rest. Slamming all my lower body strength onto the no-longer powered brake pedal and all my upper body strength into pulling the Un-powered steering wheel to the right, I managed to get to the shoulder, slow to a stop, and prevent my second serious accident in two years.

As I sat there collecting my thoughts, seemingly out of nowhere, a man tapped on my window. Probably the highway patrol. (Did he want his car back?) With no cell phone back then, maybe his police radio was how I was going to coordinate the assistance needed to get my useless hunk of metal safely off the turnpike or back driving on it.

“Sir, I saw the whole thing and just wanted to make sure you were OK.”

After asking me a few questions, the stranger—not with the highway patrol after all—suggested I pop the hood so we could look at a few things. When we peeled back enough bits to see the inner workings of the carburetor, the stranger pointed to a tiny hole drilled through a flange of metal on top of the device and asked, “What do you suppose used to go right there?”

I had no idea. And maybe neither did he. He began to flip the metal flange up and down as if taking the measure of its helplessness.

“From the looks of it, I imagine there used to be a small spring holding that flange down. In these old cars, the gas pedal is spring-loaded, so you don’t have to push so hard to speed up. Without that spring, the pedal plunges straight down.”

“Go look for it.”

It was not the stranger’s voice.

Without hesitation, I told the man I’d be right back.

“You’re going to try to find it? It must have broken off a mile ago!”

“Give me just a minute.”

I retraced the path of the car, eyes scanning the haystack that was the shoulder gravel and outer edge of the pavement. Not at all surprised by my good fortune, I found the spring lying on a dirt patch in a clearing of the shoulder gravel not 50 yards up the turnpike. The tiny coil must have taken its time to tumble through the rest of the engine before falling to the ground. The stranger, a self-proclaimed “classic car tinkerer,” then produced a pair of needle-nose pliers from thin air to fashion from the spring a new “hook” to attach it to the carburetor. The old car as good as new; I gushed and gushed before driving away, blessing my old police cruiser, the helpful voice from the Quinta Essentia, and the car tinkerer.

***

My encounters with strangers have not always been so dramatic. A year after The Case of the Out of Control Police Car, I was walking to my gate at Lambert Field in Saint Louis when I was approached by a woman who noticed the latest John LeCarre under my arm and wondered if I would allow her to gift me the latest Jeffrey Archer. “I just finished it. If you like LeCarre, you’ll love Archer,” was all she said.

Don’t be afraid to try again

Billy Joel, The Stranger

Everyone goes south

Every now and then

Between 2013 and 2017, I commuted to work from Maryland to Switzerland, which involved monthly flights between Dulles Airport in Virginia and Kloten Airport in Zurich. Despite the complexity of international travel, and because the Swiss designed everything they touched to run as smoothly as possible, I always endeavored on those trips to navigate my “commute” as mindlessly as driving to work in DC, sometimes even playing the “Sleepwalk through Security” game to see if I could also navigate the obstacle course of one of the busiest transport systems in the world—with its interconnection if planes, trains, and automobiles—without thinking.

One morning ahead of my return flight from Zurich, I was abruptly “awakened” from my “zero-stress, don’t-hassle-me zen state” when a fellow traveler appeared to cut in front of me just as I was approaching one of the numerous ID checks ahead of boarding. This was toward the end of my time in Switzerland, making it something like the 30th time I had been through this particular checkpoint. It meant I had earned a kind of fast-track status that allowed me to pass through security without stopping. But when my privileged bubble suddenly burst, my sympathetic nervous system instantly engaged. I felt egged to say something innocuously mean like, “Excuse me?”

“I’m so sorry, sir. The security agent asked me to come forward. I had no intention of cutting you off. Here, you go on ahead.”

I was so taken aback by his humility and so embarrassed by the lack of it in myself that I could only manage a, “No, of course, you go. My mind was somewhere else.” This was true. Since I was pretending not to be at the airport at all, my words were technically accurate. But at the moment of truth, my mind was only on the privileges this man had just stripped away for himself.

“But I insist,” the stranger continued. And he deliberately moved behind me, giving me no alternative than to take my “VIP” position ahead of him. But his deference did not end there. As we made our way through security together, sensing the genuine humiliation of my selfish blunder, he broke the ice with questions about my journey that day, whether I was coming or going, healing compliments on the Swiss whose airports always seemed to run as smoothly as their train stations. It was as though he wished to give me an opportunity to wake up and become a human being again, see that magnificent airport for what it was, and enjoy something as simple as making polite conversation with a stranger.

As we parted, he to the right, I to the left, I found myself looking in his direction, naïvely hoping we might be on the same flight back to Washington. I had a desire to see him again. To be more like him. I was so ashamed of my earlier behavior that all I wanted at that moment was a second chance to apologize for my thoughtless, arrogant, zombie act.

Or was it that in blending the well-worn wisdom of Jesus and Gandhi, to be the stranger I wished to meet in the world, I wanted to be more than that to those kind people?

Over the years, the strangers I have met in the middle distance between where I am and where I am going have been too numerous to count. There was the train conductor in Switzerland who, after I had missed my stop for not having enough German to know better, literally backed up the train, which had been shunted into a side branch from where it would be too dangerous for me to disembark.

There was the boy from Connecticut, whose name I later learned was Jamey Rosenfield. It was 1974 and our first day at Boys’ Nation in Washington, DC. Jamey had been up early to serenade those of us from the west still jet-lagged at 6:00 AM with a full set of bagpipes blaring in the small space of the halls of the American University student dorms. The business of that first-day session began by electing a party chair who would conduct the rest of the week in what was designed to be a learn-while-doing experiment in democratic government. As soon as nominations opened, Jamey, who I had never met but who had given me his name that I immediately forgot when we took our seats together, leaped to his feet and shouted, “I nominate my good friend Scott Knell.” I had to give a brief speech, sure, but so early in the mixing bowl of 100 new “senators,” two from each state, and everyone a stranger, being nominated by the 15-minute-famous bagpiper was all it took to vault me into the leadership role of my life thus far.

And then there was Dr. Joseph Gibney. All emergency room personnel are strangers when we first encounter them. Or at least I can now imagine that to be the case. Five weeks ago, I met Dr. Gibney following a nervous drive from Urgent Care to the Emergency Department of the local hospital, the first I would ever visit “in anger.”

“I’ll cut right to the case, Dr. Gibney told me after completing some preliminary tests. “No sense in beating around the bush when it’s going to all come out, eventually.”

Plain talk like that could mean only one thing.

“I get impatient when the Urgent Care folks send us their mystery cases. They mostly just waste our time. But in your case, I’m glad they did. In fact, when you get out of here—and you will, eventually—you’ll owe the Urgent Care physician a bottle of wine as she just saved your life by sending you over.”

For the next five days, I would be cared for by dozens of newly minted strangers whose only object, or so it felt to me, was my healing and well-being. They were all around me, 24-7. I noticed them, of course, but in those first few hours in Emergency, I was too shocked by events to view them as anything other than medical professionals going about their business. But after Dr. Gibney explained in detail, even drawing a picture, of what had brought me to his acquaintance, he asked if I had any questions.

I only wanted to know his name. Aware that I was in a life-or-death situation and cognizant of being inside a system that appeared to run more smoothly than even a Swiss airport, I did not want to sleepwalk my way through this encounter. After being admitted, I wanted to know the names of all the doctors, nurses, techs, radiologists, food bringers, and floor scrubbers—all of them. And as I lay in my hospital bed, night after night, without the aid of paper and pencil or means to write, I made a game of remembering each of their names. Megan, Aimee, Derek, Ike, Bella and Bella, Dint, Toniera, Sunita, Dong Mei, Patricia, and many more, including non-strangers like Jeff and Glen, who kindly visited me between their cases. And each time I saw any of them, I made a point to say their names.

“Morning, Damascus. Right on time, Victor. You’re in early, Tina.”

Was it because I didn’t want any of the unselfish people who worked 12-hour shifts on my account, including in the middle of the night, to remain strangers to me? Did I feel a desperate need not to be just a stranger to them? They were saving my life! Was it to thank them for their care that I insisted on at least remembering who they were? And saying it at every turn?

Thank you, Malik.” “Thank you, Mike.” “Thank you, Deedee.”

Or was it that in blending the well-worn wisdom of Jesus and Gandhi, to be the stranger I wished to meet in the world, I wanted to be more than that to those kind people?