Thomas Aquinas argues for deliberate will. René Descartes thinks and therefore is. Celine Dion belts My Heart Will Go On. But sometimes, the body just does stuff.

Can analysis be worthwhile?

Paul Simon, The Dangling Conversation

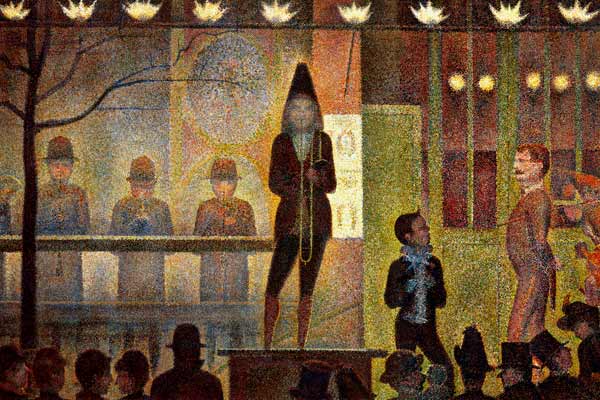

Is the theatre really dead?

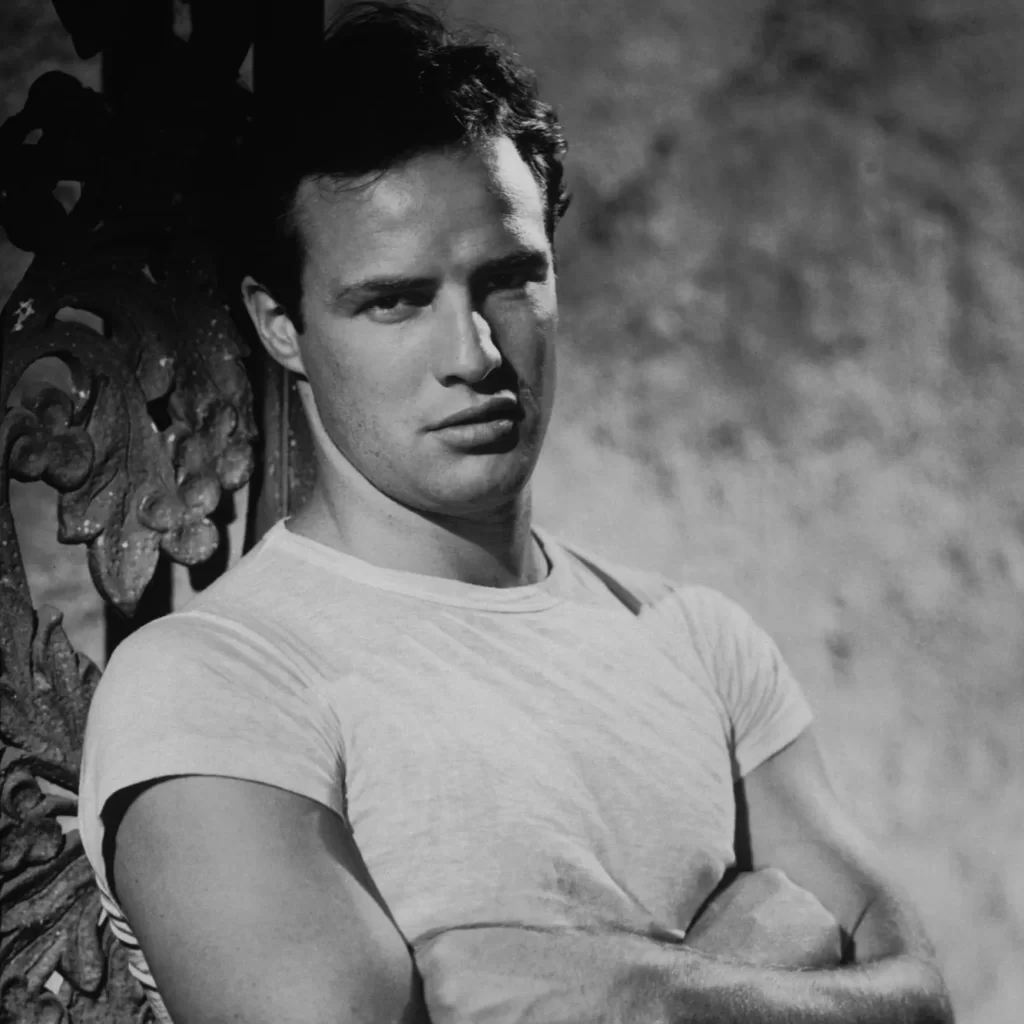

Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire, 1947

Photograph from Warner Bros. / Getty

In my sophomore year of high school, I thought it might be fun to be in a school play. I hadn’t been on stage since my command performance as The Pig in my kindergarten production of The Little Red Hen. (I can still recite my big line: “‘I won’t,’ said the pig!”)

Auditions for Thornton Wilder’s Our Town consisted of a cold reading from the classic soda fountain scene where Emily and George stumble into their blossoming attraction for one another over a couple of milkshakes. To read for George, I needed an Emily. An unknown to the theatre set, I was mercifully paired with a good sport who knew my older sister. And on we went.

After my chilly reading and before I could leave the stage, a second Emily, with whom I had no family connection, asked if I might please read with her as well. Initially flattered—my first reading must have raised at least one eyebrow!—I was happy to reprise my attention-getting audition. But when a third Emily and then a fourth asked if I could also be their George, I did the math and realized that what I mistook for flattery had been desperation. I auditioned with 22 Emilys for that play. It’s how I got into my first high school show. Just not that one.

Before posting the cast list for Our Town, Ray Jones, the high school drama teacher and a friend of my mother—they sometimes did community theatre together—deftly approached the subject of why I had not been cast as the show’s leading man.

“When Emily and George sit down at the malt shop, it’s important that George be—how do I put this delicately?—the taller actor. Before you take on a play like Our Town, you have to ask yourself, Is there an Emily in the school? Because if there isn’t, why bother? This isn’t Broadway, where people come from all around. It’s Provo High School. There’s either an Emily or there isn’t. And we have one. But she’s taller than you are. Things like that can trip up an unsophisticated audience. I’m sorry to have to tell you but our Emily, the Emily—dancer Gigi Ballif; I believe you’re friends with her younger brother Phil—has you by a few inches.”

“Why not just line us up tallest-to-shortest and push all the little people into the sea instead of making me read the same corny lines 22 times?” I didn’t say. I only read for George as that was the only part on offer that day. Nor did I suggest that “There must be roles for boys or men of average height in a play about an entire town.”

(Later in my high school performing career, during a rehearsal for The Merchant of Venice that was not going well, Jones was beginning to lose patience with my youthful portrayal of a grown man.

“Holy Stratford on Avon, Batman!” he mocked, more for levity than malice but nevertheless betraying his earlier reluctance to cast me in Our Town. I was just a kid.)

***

In those days, when a sports referee knowingly misses a call on one team, we used to call when he hurriedly blows the whistle to make an equally bad call against the other, a gimme. In my junior year, my gimme for reading George 22 times was a minor part in Look Homeward Angel, a myopic about the writer Thomas Wolfe. My first real high school role taught me two important lessons about the theatre.

First, un-tall male actors show up to the school auditorium day after day mostly to sit around waiting to go on stage to rehearse their fifteen seconds of local fame. It’s too dark to read anything, so homework is out. And unless one is overly interested in improving one’s craft against the day he will be cast in a role of average height—”Not I, said the pig”—hanging on every word the director is up there imparting to the tall and taller, I wasn’t exactly thrilled to be there. And Ketti Frings, the woman who wrote the prize-winning script we were rehearsing? Where was she? While I was bored silly day after day slumped in an empty auditorium in case my name was called, she was probably tanning herself on a beach somewhere collecting royalties. Instead of being an average-height actor, it might be equally possible to aspire to become an average-ability playwright.

The second thing I learned by sometimes being on stage in high school was how one person could turn into another person using an acting method called—wait for it—The Method.

“We, some of the guys backstage and me—we used to go down to the boiler room in the theatre and horse around, mix it up. One night, I was mixing it up with this guy and—crack!”

Marlon Brando, the New Yorker, November 9, 1957

My big scene in Look Homeward Angel was shared with a senior actor named Ray Ivy. I don’t recall what happened in the scene or any of my lines (which were few, I’m sure, though thankfully, they didn’t involve a pig). What I do remember was the story Ray Jones the director, told Ray Ivy and me about the time Marlon Brando, Kim Hunter, Karl Malden, and Jessica Tandy headlined A Streetcar Named Desire on Broadway in 1947.

“Did you ever wonder why Marlon Brando’s nose is so crooked?” Jones asked Ivy and me during the rehearsal of our little low-energy scene?”

“They’re a year into the run. Our show’s going to play for a whopping two weeks. Can you imagine doing the same show night after night for a year? So Elia Kazan hands out boxing gloves one night and tells Brando and Malden that to add a little juice, they go downstairs to the boiler room and knock each other about between scenes.”

“Sounds like fun,” quips Ivy, who, like Malden to Brando, has me by 30 pounds. “Where are the gloves?”

One night, according to Jones’ version—in the interview transcripts I have managed to find, Brando doesn’t name names—Malden lands a left jab that cracks Brando’s famous nose. When Brando next comes on stage as a bleeding Stanley Kowalski, Jessica Tandy, who won a Tony for her role as Blanche Dubois, doesn’t miss a beat.

“Oh, Stanley, you’re a bloody mess. Let me take care of that for you.”

Although Brando managed to hide from Kazan for a few days in hospital, there wasn’t time to properly set his nose.

“And now you know why Marlon Brando’s nose is crooked. And you also know what you two need to do off-stage.”

According to Ketti Frings’ script, my big scene with Ivy actually follows an offstage fistfight. It’s probably what put Ray Jones in mind of A Streetcar Named Desire. My first exposure to The Method was that during every backstage moment from then until the final curtain, I was figuring out clever ways to hide from Ray Ivy.

***

Method Acting, pioneered by Russian theatre theorist—there’s a double meaning in that1—Konstantin Stanislavski, and since practiced not just by Brando and Malden but a host of other prominent stage and screen actors—think Carrie Mulligan, Glen Close, Tom Cruise, Daniel Day-Lewis—was a technique that challenged an actor to put herself in not just the shoes but the clothing, neighborhood, time period, the complete world if it can be managed, of her character. So immersed in the milieu of their alter egos do method actors become that when Day-Lewis announced his retirement from acting, he cited the toll his preparation took to live literally in character, sometimes for months at a time while filming.

What began under Stanislavsky as a single theory of acting—channeling the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors of a character outside one’s own—eventually diverged into three acting schools, each targeting a specific transformative: physical, mental, or emotional, in my lexicon, Bone, Wit, and Gut. Coming out of New York City’s Group Theater, method acting principals Sanford Meisner, Stella Adler, and Lee Strasberg focused, respectively, on the actor’s inner Bone, Wit, and Gut.

For Meisner, behavior-driven acting, an actor’s physical response to those around her, as for Kazan, was the key to maintaining an always fresh, even spontaneous quality on stage. Instead of transferring what the actor conceived as the target character’s inner self as her own, roughly equivalent history—”Think of a time in your childhood when you lost a loved one”—the Meisner Technique draws out a here-and-now visceral reaction to the present physical circumstances of her target character. Encouraged to follow an unscripted dramatic structure, she eschews manufactured emotion and downplays even the actual dialog in favor of whatever bubbles up (or boils over) from what is physically emerging in the moment. After working with Brando first on Broadway and then in the film version of Streetcar, Malden complained that he never new from one day to the next what Brando was going to come up with.

***

The summer after Look Homeward Angel, I was cast by Jones—another gimme?—in a film being made by a local university’s motion picture studio. Or I should say Jones was cast in the film, and when its director, Peter Jensen, asked him if he knew someone at school who could play an obnoxious teenager, my name might have come immediately to Jones’ mind. As in Homeward, there were more important (not to mention taller) players involved in the 26-minute award-winning educational film. My high school fencing teacher, Sterling Van Wagenen, who played the part of a high school math teacher in the film, went on to produce the motion picture A Trip to Bountiful and co-found the Sundance Film Festival. Cinematographer and cousin Reed Smoot would later shoot The Executioner’s Song and the Academy-award-winning Great American Cowboy. I was just an obnoxious actor in his own-and-done film career, unwittingly rubbing shoulders with the eventually famous, in whose big scene I was to stand on a corner astride my 10-speed bicycle chatting up my new girlfriend, played by not yet discovered singer, actress, and television host, thirteen-year-old Marie Osmond, whose six-inch pumps brought to mind Gigi Ballif in a malt shop when the character played by child actor Fabian Cordoba, coming off a film that summer with Gene Hackman, rounds the corner on his 10-speed straight into my blind spot. After knocking into me and crashing my big moment with Marie’s character—

“Hey, what’s the big idea?” (“I ain’t sayin’, said the pig,” might have been Fabian’s best comeback.)

—my character just won’t let it go. For reasons known only to the screenwriter, the crash becomes a slight to my manhood that can only be settled by a long bike race through the city. I must not have been that naturally obnoxious because after ten takes into trying to film the scene, Jensen is telling me to be nastier.

“This kid all but knocked you down, made you look like a wimp in front of your girlfriend. How do you respond? You’re not gonna just roll over, are you? Show me!”

But I can’t show him. What do I know really know about acting? I’ve had bit parts in a couple of shows, is all. After the fifteenth take, Jensen, his visible frustration signaling he’s the one who’s not going to take it anymore, gets this idea.

“Scott, let’s try something new. I want you to get off your bike and run down to the end of the sidewalk. When you get there, run back just as fast. We’ll reshoot the scene as soon as you get here. Trust me. This will work.”

“Wouldn’t it be faster to ride?” It s a long city block!

Jensen just glares at me.

So I run. And it does work. I have to run back and forth a couple of times to really work it, but the energy—and requisite resentment—soon spills into my “acting.” No boxing gloves required, I am immersed, even if only for a moment, in the body of a competitive teenager whose manhood has just been challenged.

“Race ya!” I dare the kid who has just made me look a fool in front of my girl.

—Marie rolls her character’s too-cool-to-care eyes and walks away to find another beau. (I blame the script.) But I’m not sorry. By then, my body is the only force at work in the body-mind-heart game. Like Sisyphus,2 I’m driven by the only circumstance that matters to me in that instant: the one chugging deep in my bones.

***

Which of you by taking thought can add one cubit unto his stature?

Jesus of Nazareth, Matthew, Chapter 6, Verse 27

My first forays into deliberate behavior modification did not occur on stage. Half a decade earlier, practicing transactional analysis in my fifth-grade class, a school counselor egged a short-fused kid into throwing a metal chair at a classmate. (What was I doing in such a setting? My parents were informed I was part of the control group in what during the sixties had become a fashionable experiment in group therapy.)

Later on, in a high school T-group session3—two control roles out of two; lucky me—when my friend Ben Porter could no longer sit still for my rational explanation of why I refused to cast fellow actress Rachelle Pace’s sister in a school play, he jumped up so quickly he sent his desk crashing to the floor.

“Scott! You’re not listening to her feelings. Rachelle is dying over here, and all you’re hearing are her words.”

Anathema to my failed attempt to process the thoughts carried on the words flying from Rachelle’s mouth that morning, for Meisner and Porter—thinking is overrated.

“Don’t look at the script; improvise. If doing what comes naturally isn’t enough, inhabit someone else’s body for a beat.”

My wife Kari, who knew Rachelle, Ben, and me in high school, and who even tried to get into that early morning “human processing mill,” has, over the years, become my Bone coach.

“Pretend I’m Rachelle,” she will say. “Close your ears to my words. If you hear them, forget them. Concentrate on my face. What am I saying with my body? Tell me not what you’re hearing but what are you feeling?”

***

Bone never solos. It is the physical manifestation of everything intellectual, emotional, motivational, and spiritual, enfolded within us. You might hear me say that Bone leads; that in response to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, there ought to arise an equal and opposite Therapeutic Behavioral Cognition practice. But if Meisner led with Bone—think: Act first, ask questions later—it is because he knew the rest of the transformatives (Wit, Gut, Flash, and Outbreak4) would not automatically follow. Like electrons that come and go on demand as we observe them, Bone‘s ensemble stumbles onto the stage unbidden.

Transformatives are not serial, nor do they fire off in a predictable order. It’s just easier to study them one at a time. (Serially is how many of us have been trained to think.) But according to theoretical physicist David Bohm, in nothing short of a complete and simultaneous mash-up of the physical, mental, emotional, motivational, and soulful universe is absolute truth persistently enfolded away from us. In explicately unfolding it, we only think we’ve got it.5 Or to paraphrase Terry Hippolito, sounding beyond the bone is like looking for a black cat in a dark room and all the lights are out, and the cat was never there to begin with, and somebody yells, “I found the cat!”6

Imagine that, like our brain, the enfolded universe has a System 17 where it compiles such things far from our conscious ability to take them all in. Does it arrange them in a prescribed order—First, pack in the mind, then wedge in the heart, pile on the body, and sprinkle around the soul? When the compiled transformatives are invoked, do they parade around in a kind of last-in-first-out sequence? Or, like photons, light waves, tears, and Schrödinger’s Cat, do such phenomena unfold themselves to us only when we decide to observe them? And if so, how might we better note the properties of Bone, Wit, Gut, Flash, and Outbreak that make up not just ourselves but the institutions on whose stages we strut?

We need a better method. And I need to find a concrete way to write about Bone. Maybe if I ran around the block a few more times?

***

NOTES:

A draft of this post was first written in May 2023 as The Method.

- See my post, Schrödinger’s Cat Burglar, for how theory and theatre share the same Greek root.

- In Rock, Paper, Sisyhpus!, I imagine what (or if) bone-driven Sisyphus thought about while pushing boulders eternally up a hill only to watch them crash back down to restart the cycle.

- In the 1960s and 70s, the theory of Transactional Analysis, specifically the way your inner Parent, Adult, or Child engages with my same three personas, was practiced in exploratory therapeutic multi-person sessions called T-Groups.

- For an introduction to CBT and how the timing and boundary objects that conjoin the five transformatives that underpin and, in some cases, undermine it, See Bone, Wit, Gut, Flash, & Outbreak and the six posts that follow.

- In Wholeness and the Implicate Order, theoretical physicist David Bohm describes reality as either explicate or implicate. He posits that the universe we see, and by extension everything in our world, including ourselves, is most often explicate, explicit, and momentarily disentangled. The actual universe is most often enfolded to us, hidden, and at any rate too entangled to grasp, choosing to reveal itself according to its own pleasure, whatever such a concept means to a universe.

- For the short version of how truth reveals itself only when properly observed, see my post, Schrödinger’s Cat Burglar.

- For a lay explanation of how the brain compiles not just muscle memory but memory-memory, see my post First Person Metacognitive. For the whole enchilada, see Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking Fast and Slow.