[For Karl]

When the knell tolls, like a scatter of pebbles across this archipelago of human being, its resonant frequency finds its way into not just my heart but yours beating but a stone’s throw away.

We’ve used half a moon

Karl Joseph Savage

Uselessly

Happily

The day I met Ray Bradbury in 1982, he gave it as his ultimate vision that there might one day be a museum on every street corner.1

“Perspective is everything,” he said. “It’s crucial that as a civilization, we erect and hold always before us the pantheon of our accomplishments and especially our failures.”

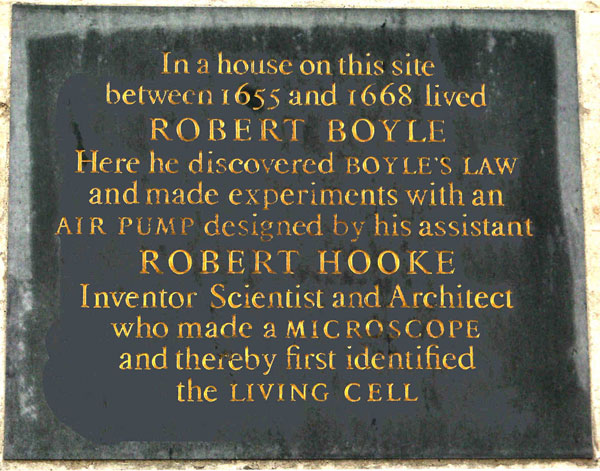

A quarter-century later, a license-plate-sized museum posted at eye-level on a limestone wall just north of Oriel College stopped me short on the High Street in Oxford, England.

It was the day after Guy Fawkes Night, that oddly satisfying anti-holiday when the British celebrate a fiery event that never actually happened.2 The non-stop explosions robbed me of sleep, and the next day I zombie-walked the city of dreaming spires. Opposite the Radcliffe Camera, I came to the commemoration of an event that not only really happened but changed everything Robert Southey taught us about being made from snips and snails, sugar and spice.3 The electric thrill I felt at “and thereby first identified the LIVING CELL” compressed three-and-a-half centuries of scientific progress since Hooke’s time at Oxford into a singular idea: when clambering the shoulders of prophets, it is peevish to pass off as our own the certainty with which we lay claim to how things then, now, and yet come to be.

Any physician who swears by Hippocrates tiptoes across the epaulets of the medical giant who, before demanding they “first do no harm,” advised his pupils to “declare the past”—truly proclaim it; not just how they remembered it, or how it was incompletely or inaccurately described to them by others.

Hippocrates next words were equally unequivocal. “Diagnose the present.” Don’t flinch or look away from the face of hard (or bloody) things. Stare down reality precisely as you encounter it. If you can do so, touch it. If you can touch it, press hard.

He continues: only when you combine your most vivid recollections of the then with your most sanguine observations in the now, will you be equipped to take that terrifying leap into the yet: “Foretell the future.”

Hippocrates was Aristotle’s giant, though only by a decade. On the shoulders of the Father of Medicine, Aristotle postulated that living tissue differentiated itself long before organs did. Whereas Hooke was first to see the naked cell, without Hooke’s giant—Dutch inventor Zacharias Janssen who built the first known microscope—Hippocrates, Aristotle, and all who lined up for two millennia after them were able only to reduce living matter to a handful of household objects—think earth, water, air, fire, and the like. For natural philosophers and alchemists all the way down to Isaac Newton (who graduated Oxford just a few paces from, and in the same year Hooke left his home on the High Street), the material order began and ended with the ground they walked on, the rain that turned soil to mud, the heat that baked mud into pottery, the wind that dried the pots to practical use, and a fifth element the ancients called the quinta essentia, that floated like either into and out of human implements from and to the rest of the cosmos.

Thanks to the miracle of magnification and its temptation to reduce the four formative elements—earth, water, and air, and their catalytic converter, fire—ad absurdum, our current periodic table now boasts 94 naturally occurring essentia—think C for carbon, H for hydrogen, O for oxygen, and MO for molybdenum; another two dozen elements we have managed to synthesize from them; and even a few fictional ones (think AH! for the element of surprise4). But in the four centuries since Hooke, the quinta essentia—which made its way into English as quintessence, remains an invisible, indivisible, and controversially argued placeholder for the mysterious nature of the perpetually ineffable.5

***

We speak in development economics of the global-local partnership. When we enshrine bumper sticker wisdom like Think global; Act local, we picture multi-national concerns reaching into neighborhoods on the same scale that a 44-college university like Oxford can sponsor the creation of a machine that will one day look so deep beneath our skin that naturalist Charles Darwin foretold it might unseat his own perspective-busting hypotheses.6 The African proverb that promises/warns us that picking up the second end of the stick is the reward for picking up the first is given as a tale of both enlightenment and caution. On the business end of Janssen’s microscope, Hooke opened up both a cornucopia and Pandora’s box of knowledge.

The mighty ships tore across the empty wastes of space and finally dived screaming on to the first planet they came across – which happened to be the Earth – where due to a terrible miscalculation of scale the entire battle fleet was accidentally swallowed by a small dog.

Douglas Adams, The Hitchhikers GuidE to the Galaxy

Of all the leaps of change across and throughout this middle distance, the co-silient (jumping arm in arm) is the most outlandish, the most complex to execute, the riskiest to its stated endeavor, at times the most terrifying, and in the end the most rewarding by a mile. Looked at another way, to grab the other end of that African stick is to break away from long-held traditions, and beliefs, in exchange for something completely xeno. Consider the following sticks: Janssen’s microscope; Hooke’s living cell; Darwin’s reputation-threatening declaration. On their other ends, the research of Columbia University sociologist Jack Mezirow suggests we find—and then exploit—the vulnerabilities and volatilities of uncritically assimilated worldviews that clash with our recollections of the past, perceptions of the present, and musings on the future.7 The surest way out of one’s comfort zone? Invite someone else into it.

***

When, twenty years ago, Kari and I hoped to escape our comfortable orbit to give our youngest children something closer to the salad days their siblings once endured, we dreamt of Africa.

“Wouldn’t it be something to just walk away from all this and start over someplace more basic?”

In the initial arrogance buttressing such a dream, not to mention what I now recognize as an embarrassingly obscene, white savior approach to international development, I had the racist gall to look down at all the places I had never visited through the wide end of the American telescope.

“How could my over-the-top professional chops, working French, and an MBA from an American football powerhouse be anything but a boon to an impoverished, third-world [read inferior] corner of the planet?” I crowed, fortunately, only to myself. “They’d be lucky to have me.”

But a dozen shocking rejections later, the most galling from an organization I volunteered to join without pay, was the first step backward in the many I would need to set my big head straight about who I really was—and wasn’t—vis-à-vis the rest of the world. It also helped to meet a benevolent stranger leaning in from my wayside and kind enough to break protocol to read me into—or, in my case, out of—the picture.

“Perhaps it’s time somebody explained to you your predicament. Through an accident of birth, you are the wrong color, the wrong gender, and from the wrong side of the equator even to volunteer in this sector.

“My advice to you, Leopard,” this kind but direct finger poster was spelling out to me, “is to go into other spots as soon as you can.”8

A few years after abandoning my neo-imperialist campaign to live and work in Africa, she uncrossed my stars and came to me instead. At the turn of the century, a young Ghanaian entrepreneur named Elliot Amoah pitched me an idea for micro-franchising the Internet across Africa. The ten-year, eye-popping adventure that followed—

“Scott. This is Africa. Forget everything you know about every place you’ve ever been!”—

opened my shuttered peephole to an entire universe outside the cave.

“And you won’t understand until you get on a plane and come over here.”

In his patient partnering, Elliot opened an effectual door that prepared me for Peace Corps in 2016. And Peace Corps led me to Prosper in 2017.

My change partners, Prosper Atanga and Azeddine Hibaballah, (standing far right), showed me that to augment a cashew crop in Ghana, or grow tech in Morocco, I might first plant a seed in Washington, DC.

Like Elliot, when I met him, Prosper Atanga was a young Ghanaian innovator who understood the mysterious riddle of partnership, that to thrive individually takes a village and where none exists, you build it. With Peace Corps to namedrop, he coaxed Orange Technology and IBM to sponsor a Let Girls Learn hackathon that kept children in school even as their fathers (and other men) forbade it. Pearl Buck taunted neo-Luddites that “You can tell your age by the amount of pain you feel when coming in contact with a new idea.” When I first came in contact with the notion of a hackathon, I felt not so much a twinge of pain as I pictured a cluster of techno-teens chugging pizza and beer while breaking into a heavily fortified government computer network in the middle of the night. A hackathon’s a party alright and there is plenty of pizza and Diet Coke to go round. But its ethical hacking is not into forbidden zones but complex problems that can only be solved in packs. Hackathons are crowd-sourced innovation jams, or as my son-in-law and children’s play expert Kenneth Wright calls them, take-apart-ies, where social problems are deconstructed—hacked—then improved, then hacked back together in no time flat, usually over a weekend.

For his first Peace Corps hackathon, Prosper brought together Peace Corps volunteers and Ghanaian public health workers to create a PeaceMalaria gaming app that mimicked the malaria lifecycle in order to slow the spread of the disease through increased disease awareness.

He next launched, Let Girls Learn, which targeted low female enrollment in school to help break the cycle of poverty often perpetuated when young women were kept from education opportunities by the actions of the men in their lives. Hackathons are sometimes run as competitions between multiple teams attacking different aspects of the same problem. One team conceived a hack that leveraged traditional Ghanaian respect for authority into the creation of a special code that could be entered into a prospective student’s mobile that would then trigger a pre-recorded message sent to her father’s phone.

“Hello. This is President John Mahama of Ghana. Let me share with you how important it is to our country, our people, and your family that your daughter be encouraged and supported in her noble desire to receive a lifelong education…”

In a follow-up to Let Girls Learn, Prosper enlisted IBM to provide materials for volunteers to assemble and load sub-hundred dollar Raspberry Pi’s9 with content developed to improve gender equity in teaching, reproductive health, feminine hygiene, and continued engagement in education, a prototype of which eventually made its way to the Obama White House to showcase Peace Corps’ game-changing work.

The year Prosper invited me to pick the winner for an agricultural hackathon targeting the diseconomy of information between buyers and sellers of the Ghanaian cashew crop, over eighty local software

engineers, and GPS specialists, joined up with cashew farmers and Peace Corps volunteers. The winning hack exploited satellite imagery to help cashew farmers better predict crop yields and storage requirements, while a follow-on app enabled them to share pricing information with each other in an attempt to level the diseconomies of information exploited when unscrupulous corporate buyers sought to use the naivety of erstwhile uninformed crop sellers to an unfair bargaining advantage. The next year, Prosper crossed a couple of borders to help our mutual friend Azeddine Habiballah conduct a tech expo in Marrakech.

Reviewing Prosper’s body of development work this week—for links to YouTube highlights, see the footnote below10—I have asked myself, not for the first time, whether my running interference for his projects in Washington or convincing his supervisor in Accra to grant Prosper time away from his core duties to conduct his annual, spare-time hackathons made a difference in his outcomes. I doubt it. In fact, the longer I consider the balance of any benefit I might have brought to Prosper’s work against what I personally picked up just watching that work, found me wanting. Prosper helped me understand better than any book on social innovation I might have read or lecture sat through on community development that no matter how desperate the problem, how willing the participants, or how clever the solution, without the audacity to break away from the pack, buck the system, go against the grain—insert your favorite metaphor here—institutional change will never progress beyond talk, let alone reach the tipping pointed disorienting dilemma that propels us off our dimes toward resolution, without first engaging that institution, declaring its past, diagnosing its present, and foretelling its future. Prosper not only channeled Mezirow without ever hearing of him, he effectively mentored a plodding pupil over twice his age on how to outbreak the accidents of his birth to engage in work outside his comfort zone. The nature of any partnership is that when water passes through the pipe, it is not just the fertile field on its business end that gets wet. There is also the pipe to consider.

***

When the knell tolls, like a scatter of pebbles across this archipelago of human being, its resonant frequency finds its way into not just my heart but yours beating but a stone’s throw away.

My odyssey to clamber out from behind my solitary peephole to more fully observe the quintessential within and around me has been shaped by a sonorous metaphor, not from Douglas Adams or Danny Archer10 but of the 16th-century poet John Donne. The first time I encountered his counterintuitive accusation in For Whom the Bell Tolls, my ear rested a beat longer on its outbroken peeling of the death knell, and not solely because of my nominal connection to such a sound.11 Its low and elongated frequency, designed to pierce the atmosphere and bring sorrow to ears and hearts for tens of miles, tolls across the centuries from a decade in the 17th century when Donne, Hooke, and Newton all walked the High Street.

No man is an island,

John Donne, No Man Is an Island

Entire of itself;

Every woman is a piece of the continent,

A part of the main.

If a clod be washed away by the sea,

Europe is the less,

As well as if a promontory were:

As well as if a manor of thy friend’s

Or of thine own were.

Any person’s death diminishes me,

Because I am involved in humankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls;

It tolls for thee.

(gender substitution mine)

***

In refreshing Aristotle’s terms of household art—Bone for Earth, Wit for Air, Gut for Water, Flash for Fire—I have chosen to rename Quintessence as well, which in our age of superlatives no longer means the fifth anything but has become the modern shorthand for the absolute essence of everything, a standing invitation to consider Mezirow’s imperative to break away from what we know in search of what we might never. Because to conceive of something beyond ourselves requires a leap above the head and shoulders of even our giants, I call the new quintessence Outbreak. Whenever I use that term in this blog, I am pointing beyond the touchable, the knowable, the feelable, and the will-able to something within but also beyond our four-legged table of Bone, Wit, Gut, and Flash.12

“Outbroken” is a word that came to mind one morning this summer. As I sometimes do, I had been pondering—dreaming, probably—about the ancient idea of Quintessence. As did the natural philosophers, I see Outbreak as the thoughtful respect for and response to the workings of outside forces that simultaneously abide within and extend from one’s natural identity into the fifth essentia. As such, Outbreak is more akin to the forces behind the events leading to a state closer to heartbreak than, say, jailbreak. The words of my favorite anti-John-Donne, folk-rock poet notwithstanding—

And a rock feels no pain

Paul Simon, I Am a Rock

And an island never cries

—it is in submission we admit to being not the know-alls, be-alls, and do-alls on this planet; neither its giants nor its islands.

***

In a few weeks’ time, I will join up with a community development organization attempting to understand and do something about violence against women, juvenile delinquency, and an ill-understood phenomenon called desistance—think how even the most hardened among us can be brought to a soft landing away from what we euphemistically label “correctional institutions.” Not unlike my dreams of African grandeur, I will again, I’m sure, be tempted to think that because I am fortunate not to have been a victim of violence or a prison inmate, I will be their immaculate savior. I hope by now I have learned that it will be on their shoulders that I first clamber for a proper point of vantage. And at the end of it all, it will be I that softly lands.

***

NOTES:

- The circumstances of my meeting writer and futurist Ray Bradbury in the fall of 1982 can be found in my post, The Proper Aim of Art. Bradbury told the story of how, “In the early 60s following Kennedy’s moonshot speech, I kept this little notebook in my pocket where I’d write down people’s thoughts about it. At cocktail parties, whenever anyone poo-pooed the idea of putting a human on the moon, I’d jot down their name and number so that when The Eagle landed, I could call them up and gloat. And you can be sure I did”

- An account of what Guido (Guy) Fawkes did—or failed to do—as part of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 can be found here.

- Robert Southey is purported to have written the children’s nursery rhyme that begins with the question, “What are Little Boys Made Of?”

- “AH: the element of surprise.” I wish I had devised this clever play on the periodic table. It comes from a T-shirt I bought my son David at Next to Nothing, a shop in Oxford’s covered market literally next door to one called Nothing. Exiting the covered market on the High Street, one can just make out Hooke’s street corner museum across the way.

- Like Newton, Einstein attributed the gap in his knowledge base to something he called Dark Matter, an actual substance only recently proven to exist.

- In Darwin’s Black Box, biochemist Michael Behe, purports that Darwin once said that were there ever to come along a subcellular microscope, his transient theories might be refined—even displaced—by those based on observations unmakeable in his day. Though it would seem to make sense that a mind as nimble as Darwin’s could go there and back, I have yet to substantiate Behe’s claim, though I’ve only asked Google about it.

- Jack Mezirow was an American sociologist and Emeritus Professor of Adult and Continuing Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. Mezirow is widely acknowledged as the founder of the concept of Transformative Learning, a change strategy that exploits the disruption of uncritically assimilated perspectives through organic or orchestrated, disorienting dilemmas. For more on disorienting disruption, see my post, Leapin’ Leopards!

- In Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Story, How the Leopard Got Its Spots, to save the big cat from starvation, his friend says, “The game has gone into other spots: and my advice to you, Leopard, is to go into other spots as soon as you can.”

- In the 1990s, just before his era-ushering ground-breaker Being Digital went to press, MIT Media Labs founding director Nicholas Negroponte issued a challenge to the techno world to produce a sub-one-hundred-dollar portable computer for use in developing countries. The world answered Negropont’s One Laptop Per Child challenge by inventing something called a Raspberry Pi. Its tiny processor could power a handful of essential functions that, for Peace Corps, and with the help of Arizona State University, could bind to a one-foot square solar panel to produce an Internet-in-a-Box into which a subset of knowledge could be remotely loaded to create a portable worldwide web anywhere on the planet.

- To see Prosper’s Peace Corps hackathons in progress, check out: Prosper’s Let Girls Learn Hackathon; Michelle Obama on Let Girls Learn; Cashew Farmer Hackathon;

- Danny Archer was the name of a character in the Edward Zwick film Blood Diamond, played by Leonardo DiCaprio. As an explanation for the strange ways of Archer’s world, he would sometimes just shrug and say, “TIA, This is Africa.”

- My surname is not indigenous to my biological roots. It was grafted into them during metamorphism involving my great-great paternal grandfather, né William McMillan, a Scot from Northern Ireland. For reasons too convoluted to go into here, after coming to America, McMillan changed his family name to Thompson, whereafter his sons changed theirs to Knell, the name I eventually inherited.

- Outbreak is that part of us that hovers—inexact word, but it’ll do for now—within and about our periphery. In the seven-part blog series that begins with Bone, Wit, Gut, Flash, & Outbreak, I describe the five elements not as internal to themselves but as boundary objects that, like the conservation of mass, energize each other, to effect a kind of perpetually changeful existence. The resulting duality allows me to envision Change not as Being’s opposite but as the complementary face of the same coin. The other way Outbreak is different than the four other internal properties of identity is that when they mix with themselves, we can pretty much predict the results. As children, we combined water and earth to make mud pies. (Fun fact: At one point in his Odyssey, Aristotle ascribed the abiogenetic origin of life to nonliving mud.) As a four-year-old, with the abetting of my five-year-old senior neighbor, I once combined earth, fire, and air to burn down ten acres of woods near my home. But the ancients would say Quintessence was of a higher order of matter. They compared it to ether, which they viewed the same way Star Wars fans understand George Lucas’ in-and-all-things Force in and all things and for the same reason. For alchemists, when combined with baser elements, Quintessence assisted base metals in their breaking into a thing of magic, culminating in a bad rap these days for greedily aspiring to spin mud into gold. But real alchemy was practiced in pursuit of spiritual—not physical—transformation, Quintessence, the bridge element to the eternal. (It’s sometimes convenient for history to oversimplify, even demonize, the misunderstood.) For me, Outbreak is the simple (and sometimes risky) act of extending that part of me that extends beyond my base metal and alloying it with another’s Quintessence. For more about my thoughts on Outbreak, see my posts, The Boys from Brazil, Irrational Will, and Falling Objects.