Want to change your spots? Not until we see the past for the feral creature it is and, with trepidation, let it into our house, train it not to bite our guests, and give it its own dish will we reduce the odds its jaws will one day spring back upon our necks.

Rudyard Kipling, How the Leopard Got Its Spots

The game has gone into other spots: and my advice to you, Leopard, is to go into other spots as soon as you can.

Do leopards leap? I’ll answer that imponderable by reviewing the way we count crows. But first, a trivial pursuit.

Nouns of assembly—think a barrel of monkeys, a pack of dogs, a pride of cats, a murmuration of starlings—owe their naissance to images called to mind when named species are either gathered, hunted, caught, or killed. Picture a farmer’s drove of pigs, a piscator’s school of fish, a trembling hunter’s sleuth of bear, and now Edgar Allen Poe’s murder of crows. My favorite term of venery is the alliteration reserved for the collection of a particularly elegant flock of birds.

“And over here, ladies and gentlemen, please find wading on one leg along the banks of the great, grey-green, greasy Limpopo River, a flamboyance of flamingos.”

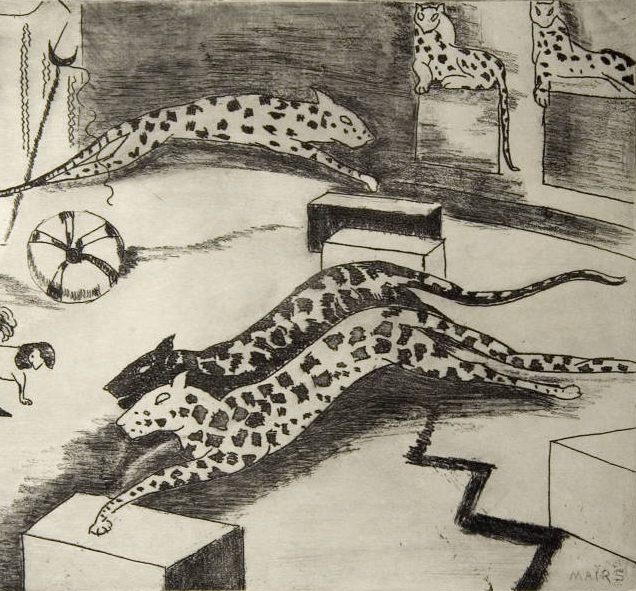

Leopards, it turns out, hunt in leaps. Perhaps in conceiving his Just So Story, How the Leopard Got Its Spots, Kipling calls up similar imagery when he pushes the big cat to a leap of change so drastic its new floral camouflage spares it from starvation. Kipling is merely answering Jeremiah’s three-thousand-year-old quandary: Can a leopard change its spots?1 His where’s-your-breakfast retort is that it depends on how hungry it is. For the purpose of venery, the only inky leopard in my life is I; the only proverbial question worth answering is whether I can muster the strength and know-how to leap out of my own skin once in a while, leaving behind my past, present, even my future like so much loose clothing. Is there such a thing as a change of humans? And if so, can it leap?

***

Salience, noun.,

From the Latin salientem (leaping), the quality of leaping or springing up.

The Oxford English Dictionary

The word Leap is a term of art embedded in its ancestor Salience through the cognate ‘silience. Consilience we know from Edwin Wilson’s scientific masterpiece on how the more sources of truth leap together, the more full of truth will be their unified conclusion2. Transilience enables us to leap across a divide in the same way transformatives like Bone and Wit encroach upon other boundary objects like Flash and Outbreak.3 Dissilience means to leap asunder as when the implicate whole is deconstructed into its myriad explicate bits.4 Changefulness’ arch enemy Resilience signifies a backward leap, though seldom one in a useful direction. (I can’t say if I’ve ever seen a leopard leap but I’m positive never to have seen one leaping backward.)

When, like Kipling’s leopard, we leap forward (prosiliate) to abandon our aboriginal flora and fauna for other spots, we jettison the someplaces and somethings—our Bone, Wit, Gut, Flash, or Outbreak come to mind—that no longer suit us. While true that transformation may be unwittingly thrust upon us, most of the time, we select our prosilient course of action. One reason change is so gut-wrenching, bone-jarring, wit-rattling, and so on is that for as many reasons as there are personal pasts, presents, and futures, we are wired to stay close by them. But some flights of change require quantum leaps.

Kari’s cousin Rich, a pricing pioneer and renowned expert in customer service, is an unstoppable force when it comes to training customer service professionals. After going ’round the world to field test hotel front desk staff incognito, he once told me about a tug-of-war he won or lost—you decide—over a tiny square of wax paper and its convenience store hawker, an immovable object in his own right.

So, every week I stop on my way to boy scouts at this mini-mart at the corner of Glen Road and Travilah; the one next to Dominos Pizza. And every week I buy a dozen doughnuts for the scouts so they’ll like me better when I teach them to tie the double half hitch. Been stopping there for months and I always follow the same routine: pick out the doughnuts; put ’em in the box—it’s all self-serve; I don’t touch them directly but use those little wax paper thingies to keep, you know, the goop off my fingers. After I pay, I pick up a bunch of napkins and a handful of those wax paper thingies so the boys can eat them without getting goop on their fingers. But this time the shop owner has his own idea.

“Sorry, sir, but you have to pay for those.”

“The doughnuts? I just did?”

“No, the deli paper.”

“These things?” I hold up the dozen or so wax paper thingies.

“Yes, those things.”

“I thought they were free. I get them every time I come here.”

“You mean you steal them from me every time you come here.”

Long pause while I imagine one of only two ways this standoff is gonna end.

“Come on. I just bought a dozen doughnuts. Paid you, what, ten bucks? You throw in the napkins, why not these ‘deli papers’ that cost nothing?”

“They don’t cost nothing and someone has to pay for them.”

“Well, it’s not going to be me.”

“Who’s it going to be then? You have been robbing me for some time. I pretended not to notice. But enough already.”

“Look, you know me. I come here every week. And I’ll keep coming here every week. But not if you’re going to charge me for what is clearly your cost of doing business.”

Another long pause. I continue.

“What would that be, by the way, your cost for one of these thingies?”

“Your cost, you mean. Fifteen cents.”

“For all twelve?”

“Each.”

“Fifteen cents a piece?” I’ve taken the handful of wax paper thingies out of my bag.”

“You say you have twelve? You owe me one dollar eighteen cents.”

“I can count but I’m not paying you a dollar-eighty. The whole wad probably only cost you a nickel.

“One dollar eighty cents.”

“Here’s the deal. The ten dollars I just paid you for the doughnuts—”

“Ten dollars and fifty-nine scents.”

“Whatever. If you make me pay twice I’m going to walk out out of your store right now and never come back. And if I do that—you’re good at math, consider these numbers. I’m forty years old. I could live to be a hundred. That’s sixty years of me not coming here, not paying you ten dollars a week. It’s gonna add up. Sixty years times fifty or so weeks a year, times ten bucks a week—not even counting inflation—that’s gonna be…”

“Thirty thousand dollars? You honestly expect to buy thirty thousand dollars in doughnuts from my store?”

“I might buy a flashlight every year. Maybe a moustrap. Just give me the deli papers.”

“No can do. You owe me one dollar eighty cents. Plus tax.”

“OK. Here’s your deli papers back.” I set them back on their dispenser. “The boys can lick their fingers. Guess I’ll see you, what, never? Your call.”

“Never will be just fine.”

In Rich’s book5, or one of his lectures, he tells the story of a merchant who posts two rules on the sales-clerk-side of the register so that his employees can see them when ringing up customers.

Rule #1: The customer is always right.

Rule #2: If in your view, the customer is ever wrong, see Rule #1.

Rich’s anecdote is the classic stalemate that can arise when two mutually unyielding perspectives find themselves in the same orbit. But what would happen if, as Kurt Lewin suggested, one or both of their positions could be “unfrozen” long enough to align with the other before refreezing?6 Let me illustrate how such a tug-of-war can be resolved while also suggesting (for later consideration) that the same interpersonal principles at play can also be applied to intrapersonal self-transformation.

Lewin described this dynamic according to what he called Force Field Theory, the idea that change fundamentally takes root under only two conditions: either its forward momentum overpowers the inertia that initially blunts it; or the the backward momentum of inertia takes a holiday.

Let’s suppose for a moment that after hearing out the Immovable Object, the Unstoppable Force in Rich’s example chooses the path not of opposition but vulnerability. What if, after paying Immovable Object (IO) for his deli papers, Unstoppable Force (UF) reconsiders his pledge never again to darken IO’s door? What then?

According to Lewin, when UF unfreezes his impenetrable shell—we’ll defer to a later post key questions about who or what actually does the unfreezing—he exposed his Flatland heart7 to the slings and arrows of changefulness. Before freezing it back over, UF becomes a changed man and will forever be so until moved upon again by an equal and opposite unfreezing, rechanging, and refreezing. Let’s imagine what such a transformation might look like.

The next time UF enters IO’s convenience store to feed the boy scouts, he has changed his mind, his heart, his will—his entire perspective on IO, the person. In fact, UF has experienced such a mighty transformation that I now refer to him as VF (for Vulnerable Force). IO, however, shocked by VF’s unexpected appearance but still no fool, has put up his dukes for a fight.

“So, you decided you couldn’t live without my doughnuts. You ready to buy them on my terms?”

“I am so ready I’ve also decided to pay you for the ten dozen sheets of deli paper I ‘stole’ from your word not mine—over the ten weeks before last.”

“Ah. And what about the forty weeks before that?”

“Excuse me?”

“You’ve been stealing my deli paper for over a year.”

“Are you serious?”

“Are YOU serious?”

“I’m outta here.”

The life so short, the craft so long to learn

Geoffrey Chaucer, Parlement of Foules

The problem with VF’s change of heart lies not with VF (Vulnerable Force) but with his former unstoppability, i.e., UF. VF might have walked into IO’s store, but UF still darkens his door. The mechanics for this one-step-forward, two-step-back relapse lies in what I’ll call Lewin’s Freezer. The forces that demanded the un-freezing of UF’s identity before his heart could be “open” to VF implant surgery are the same forces that will hold the new heart in place after Lewin’s Freezer is turned back in. Lewin described the first step in this dynamic according to what he called Force Field Theory, the idea that change fundamentally takes root under only two conditions: either its forward momentum overpowers the inertia that initially blunts it; or the backward momentum of inertia takes a holiday.

But what happens if, after the freezer is turned back on, the power suddenly fails? Will our change fall apart, its center unable to hold? When it does, the savvy changeful might be tempted to blame their backsliding on Resilience as they slouch into their past. In proffering a rosier explanation, the hopeful dodge the disorienting dilemmas thrust upon them, claiming to be nothing but served by Resilience: I can weather the storm. I can bounce back. I will survive this.8

In either scenario, whether receding after a hard-won victory or determined to overcome the one perpetrated against us, Resilience will soft-land us in status quo ante, a backward leap no matter how we look at it. A key question for subsequent posts will be how and when to plug the freezer back in. Like snapping a leopard mid-flight, change is a craft that takes practice.

***

NOTES:

- From the Old Testament, Jeremiah chapter 13, verse 33.

- Edwin O. Wilson, Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge.

- In Boundary Objects, the third in a seven-post introduction to Transformatives, I introduce the interplay between subelements of identity as they rub off on each other to effect self-change.

- David Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order.

- Rich Hanks, a former executive vice president at Marriott International, is known in the hotel industry as the creator of the non-refundable discount reservation. His book Delivering and Measuring Customer Service: This Isn’t Rocket Surgery! advocates using direct and real-time metrics to gauge the customer experience.

- Kurt Lewin, the “social of psychology,” was a German-American psychologist known as one of the modern pioneers of social, organizational, and applied psychology in the United States.

- In 1884, Edward Abbott devised a thought experiment where beings from our three-dimensional world interact with an imaginary two-dimensional Flatland. In Rudy Rucker’s centennial review of Abbott’s novel, he suggests that beings from a higher sphere of existence might be capable of performing, say, open heart surgery on their lesser-dimensional counterparts without breaking the skin.

- Jack Mezirow was an American sociologist and Emeritus Professor of Adult and Continuing Education at Teachers College, Columbia University. Mezirow is widely acknowledged as the founder of the concept of Transformative Learning, a change strategy that exploits the disruption of uncritically assimilated perspectives through organic or orchestrated, disorienting dilemmas.

My dad read us the “just so stories” when we were kids. I failed to read them to my kids- a regret- maybe the grandkids one day!

The message in this post is so important!

Thanks for sharing!

Never too late for Kipling. I didn’t read them as a kid. How the Leopard Got His Spots has now been canceled but can still be mined. But for a real treat I recommend Jack Nicholson’s and Bobby McFerrin’s recording of The Elephant’s Child.

My favorite takeaway from this one: One reason change is so gut-wrenching, bone-jarring, wit-rattling, and so on is that for as many reasons as there are personal pasts, presents, and futures, we are wired to stay close by them.

Amen & amen. Wired we are. It was transformative for me when I learned this of the brain.. Before then I just thought I was weak, fragile and overly nostalgic.

This one is a thinker. ?

I credit you for whatever I know about CBT. For an hour of torture–now that I have added a reading timer I can say that for a fact–read from Bone, Wit, Gut, Flash, & Outbreak (1) thru Metanoia (7) for the full effect your Frederick lecture launched back in January.

Thank you, Loren, for sharing that story. What an harrowing incident. So glad it turned out for everyone.

Thank you, also, for the email reminder about July 4, 1976. The centenary won’t get any bigger in our lifetime, that’s for sure. And the next day you to Oslo, Steve to Barcelona, and me to Geneva. Big week for the three of us. Don’t know about you, but it was only my second time on a commercial aircraft, the first time flying to DC just two summers prior. And here I am working in DC wishing I were back in Switzerland. First impressions fall hard.