Only by taking the clock out of the equation can we isolate who we are long enough to change.

Renowned cardiovascular surgeon and medical pioneer Dr. Russell M. Nelson writes of the development of the heart-lung machine, a medical revolution that made possible life-saving procedures operable only on a still heart.

We learned that if we added potassium chloride to blood flowing into the coronary arteries, thereby altering the normal sodium/potassium ratio, the heart would stop beating instantly. Then, when we nourished the heart with blood that had a normal sodium/potassium ratio, the heart would spring back to its normal beating pattern. Literally we could turn the heart off long enough to repair it and then turn it back on again.

What if, like potassium chloride to the heart, a miracle substance could be added to the time flowing in and around our entire bodies? Such an elixir would give us time to perform life-changing procedures on not just our hearts, but our actions as well. Were time to stop still, we might more readily swap out a bad habit; learn a new skill or profession; and potentially change every aspect of our life before restarting our ticking clock.

In the 1970s, I met three-time world Formula One racing champion Jackie Stewart. A mutual friend serviced his vintage roadsters, which Stewart drove on sunny afternoons around a town on Lake Geneva where I was living at the time.

Stewart, who became a racing commentator after his retirement, spoke of how for high-speed drivers during critical moments of a big race time slows to a crawl, even a standstill. When split-second timing is the difference between winning and losing or sometimes living or dying—think negotiating a hairpin turn at speed in a noisy and over-crowded field—an experienced driver can perform a series of intricate maneuvers in what for us might seem like sub-second time. But for Stewart and expert drivers like him, split seconds somehow blossom into full minutes.

There are myriad ways to slow down time. Beatles Music producer George Martin pioneered innovative recording techniques for ‘playing’ musical instruments at twice their speed but without hurried errors. He found that if he recorded the notes an octave lower at half-speed their error-free tone would change when played back double-time. Sample Martin’s ‘harpsichord’ sound on In My Life. He’s playing not a harpsichord but a piano, his ‘rapid’ fingering impossibly flawless. While you’re at it, listen for Martin’s and George Harrison’s piano and guitar ‘solo’ on A Hard Day’s Night. To speed up time, Martin first slowed it down to blend seamlessly the two instruments when mixed.

Another way to blunt time is to slim down the amount of information we process at speed. When we learn a complex skill— think driving for the first time—the brain intakes in a carload of visual cues and deliberately (read: slowly) executes manual actions against them. Only after myriad steps have been sufficiently repeated does the brain compile them to perform on-demand, automatically, like a champion driver or virtuoso guitarist, at what might seem to others as twice their normal speed.

Since the trained brain tends to follow its programming, there are several ways to teach that old dog new tricks. Try the following thought experiment and see how far you get.

Imagine you’re a high-performance racing driver and you’re wearing as part of your helmet visor a superimposed heads-up display that eliminates the need to glance down at your car’s dashboard. Before you strap yourself into your Formula One machine, look for a moment straight ahead at the horizon.

Picture there the same edge-to-edge point of vantage you always view when taking in your outdoor surroundings. Maybe it’s a landscape. Blue sky overhead. A squirrel running across the road.

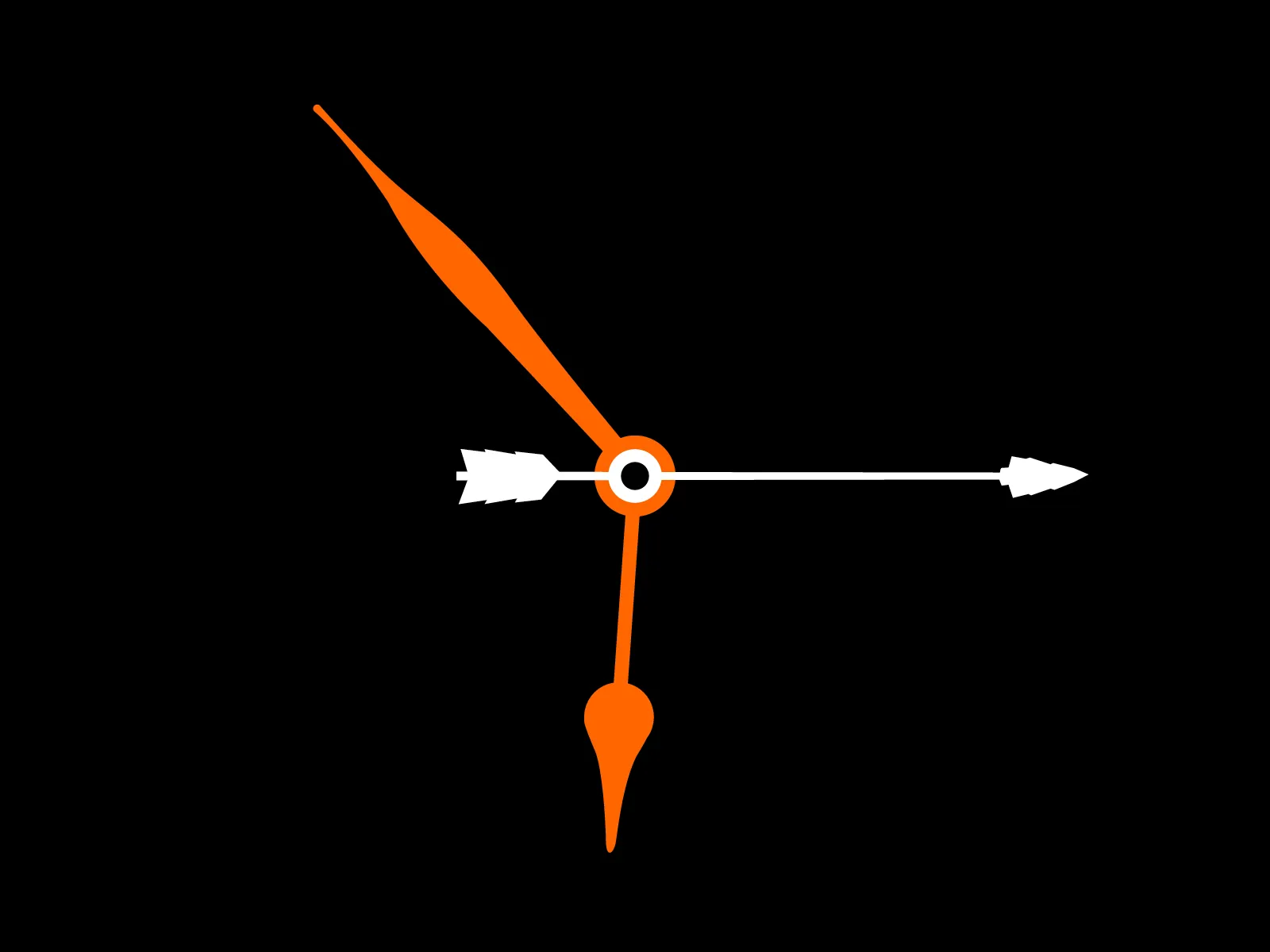

Now, see that nearly invisible clock at the bottom of the display? With a wave of your hand, blinking eyes, or just your mind, monkey with it until it displays a time of day somewhere between 10 AM and 2 PM. Think Geroge Martin’s hands on a keyboard. Or Jackie Stewart’s gloved hands on a racing wheel. Your first driving lesson.

Grounded in that moment, you now note two other visual panels on the periphery of your vision: one to the center panel’s left, the other to its right. Orienting yourself to the vanishing on the horizon, change the time stamp on the peripheral panels to sunrise. Click. Now the other one to to sunset.

And just like that you are no longer gazing across a physical horizon but a temporal one. Instead of stage left, center stage, and state right views, your three-part picture comprises morning; midday, and evening of the same image as the center panel you encountered on the physical horizon. But before you get distracted by the earlier and later panels, find the center, mid-day panel, and double-blink it.

Wo! What happened? It got larger—so large that the sunrise and sunset panels you were just admiring got pushed beyond your peripheral vision. You are now looking straight into, and only at, the present moment. But unlike the physical horizon, there’s something slightly odd going on. If there are any clouds in view they are strangely still. Where there might have been a passing bird or plane overhead, or squirrel beneath your feet there is now nothing. Humor me and raise your hand in front of your face; then try wiggling your fingers. They don’t wiggle? Can’t even see your hand? That’s because just now, you have managed not only to slow down time but stop it in its tracks.

Cool yeah?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines Metacognition as “Awareness and understanding of one’s thought processes, especially regarded as having a role in directing those processes.” Like a heart stopped for repair, the only way for the metacognitive part of our brain to focus on the cognitive part—think the part thinking about what the other part is thinking about—is for there to be a schism in the way time works for each part of the brain. Wearing your new metacognitive head’s up display, you are, in effect, standing outside of time, gazing at a freeze-frame picture of your mind’s eye—your backyard, Lake Geneva, or the last frame of life to hit your optic nerve before Time exited stage left and right. In the nanosecond it did so, you broke free from what I call Time’s Gravity—the backward pull of the past, the forward tug of the future. Like a stopped heart, you are, in that moment, at your most changeful.

What will you do next?

Wait! What does ‘next’ even mean?

This post is from a LinkedIn Newsletter called Human Changing. You can access the entire series here.