Some risks pose the probability of losing everything against the possibility of winning everything before that happens.

When I was ten, my best friend Scott Thomas introduced me to the popular strategy game Risk®. Designed by French filmmaker Albert Lamorisse the year Scott and I were born, Risk is a multi-player board game comprising a map of the world and enough warlike implements to conquer it.

“How do you play?” I asked Scott when he and his eight-year-old cousin Jeff Dyer began dumping the contents of a box onto the rug in Scott’s basement.

“You put your guns and stuff wherever these cards tell you and then roll those dice to decide each battle. Last man standing wins.”

“And it’s called Risk because…?”

“Not sure, but it’s a killer game,” said the future college wide-out and bank manager. “Trust me, you’ll love it.”

“To conquer the world, you have to take risks.” Jeff’s future lay in a UCLA PhD and best-selling books on strategy and innovation. “What if you’re a mile from winning, and you run out of ammo? I like to protect my weakest borders.”

So we played a few rounds, each lasting several hours. The cousins alternated risks, large and small, while I did my best to bleed out as late in the slaughter as I could manage. (If the world would be conquered, I was willing to do my bit.) Through it all, I learned that some risks pose the probability of losing everything against the possibility of winning everything before that happens.

More than fifty years on, I cant’ be certain which cousin chose which strategy—building up strengths or fortifying weaknesses—but I think I can still see Scott and Jeff’s two distinct paths to victory. Jeff or Scott—I’m going to go with the football player—quickly amassed so many battle resources into the southeast hemisphere that his armies spilled into the Indian Ocean before letting fly his fury on Jeff and me in a north-by-northwest direction. If Scott ran out of fighting men before finishing us off, Jeff, who deployed and steadily reinforced his positions against the attack he knew was imminent, would then return fire on Scott’s depleted forces. Having fortified his weakness, Jeff was now in a position of strength versus Scott. My armory was usually scattered to the four corners Goldilocks style: not too strong here, not too weak there. My indeliberate touch was too light to go very far but moderate enough to prevent my getting wiped off the board before Scott or Jeff took their cool-down victory lap.

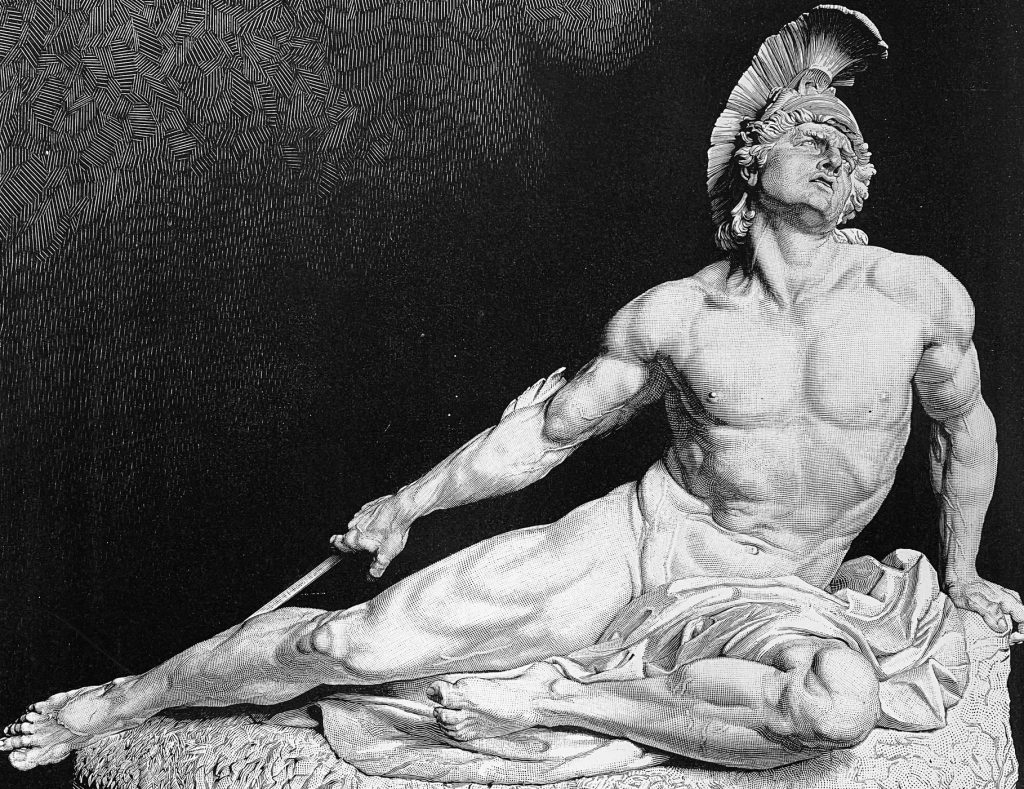

Up until the day Achilles caught an arrow in his heel, the strongest tendon in the body was called the calcaneal. What we today call our Achilles tendon is actually a cluster of three tendons stretched so perfectly that the foot can take on up to eleven hundred pounds of pressure on demand. Considered the strongest tendon in the body, the calcaneal is also said to be the body’s weakest tendon due to its concentrated tautness in crisis. When the calcaneal snaps, it’s immediately lights out for walking, often for months.

In considering industrial strengths and weaknesses, management gurus have made hay of how the Achilles heel’s strengths and weaknesses are baked into games like Risk. The same dilemmas can be found in grand personal adventures like work and life. Wherever there are risks, the all-or-nothing focus on either strength or weakness has led to considerable debate among strategists, therapists, and coaches of every stripe. Having long forgotten whose modus operandi was which—Scott Thomas and Jeff Dyer, if you’re reading this, the world is on pins and needles to know which way you roll half a century later—let’s randomly pair my old friends’ preferences with opposing sets of conventional wisdom:

SCOTT the STRONG:

- Play to your strengths.

- If you can bury your opponent with a single knock-out blow, there’s no coming back at you through your unprotected flank.

- Any investment in weakness is a sunk cost that will not increase your overall advantage.

- If you can’t be number one or two in an industry, find one you can dominate through the strengths you’ve already developed.

JEFF the JUST WANNA BE READY:

- You’re only as strong as your weakest leak.

- Even though you’ve safeguarded your assets, it’s never a bad idea to lock the front door.

- When it comes to strengths and weaknesses, your aim should be to strike a balance between the two. Leaning too far in one direction will always create an equal and opposite vulnerability in the other.

- If you can’t be the best at everything, the more at-bats you get in anything is the surest way to get a hit.

Which strategy do you favor: Scott’s or Jeff’s?

Was my seeking the middle ground between the two a best (or worst) practice?

Besides our Achilles tendon, which of our other bits is at once a weakness as well as a strength?

This post is from a LinkedIn Newsletter called Human Changing. You can access the entire series here.

Sometimes the dice rolls will favor The Strong, and sometimes the dice rolls will favor the Always Be Ready. The probabilities may favor one approach over the other in the long run, but there’s no telling ahead of time for any one game which WILL work best for that one time. A lot depends on what meta-game you’re playing. Are you in it to win? To simply explore the possibilities? To hang out with your friends? The middle of the road approach is good for some of those. I try to keep my games in the fun zone — when they start slipping into work, I may move on to other games, or give up on play for a bit and switch to work that pays.

I meant to say, I was playing card games (mostly Hearts) and “family” games (Monopoly, Battleship) when I was ten, but discovered Risk in college and enjoyed it a lot for a while, until a few too many “grind” games of where it was endless dice rolls back and forth with not much movement.