In which I begin a weekly newsletter by asking the question: What’s Yours?

To know thyself is the beginning of wisdom.

Aristotle

In the evolving experiment that is Indirections I Have Lived By, I have lately taken to writing weekly, shorter newsletter posts on the professional identity social media site LinkedIn. When the first two posts challenged readers to critically examine some aspect of their identity, it occurred to me there might be any number of questions I could yet ask.

Here, then, are four inaugural short posts of my new LinkedIn newsletter, Say the Change.

***

What’s Your Sauce? (19 September 2023)

Every organization has its very own ‘Special Sauce’. Is the same true for every person?

In my change work, I have observed that every organization highly values something it might label its ‘Special Sauce.’ By ‘sauce’, I don’t mean something spreadable for hamburgers or friable for chicken. True, while working at Colonel Sanders Mansion in Louisville, Kentucky, I observed the lengths Yum! Brands goes to safeguard its secret recipe for finger-lickin’ good chicken. At McDonald’s Headquarters in Oakbrook, Illinois, I witnessed firsthand the training and tasting kitchen where Big Macs® are still put through their paces. But companies outside the quick service restaurant industry also take pains to develop, nurture, and protect a ‘special sauce’ of their own—an offering that is uniquely theirs.

I was once asked by Universal Studios to derive an algorithm for creating the perfect motion picture. It attempted to pair a movie director with just the right title, featuring just the right stars, and wrapping the entire production with just the right marketing and distribution package to create a blockbuster on every release.

AMC theatres once asked Steve Shoyer and me to build an AI to assemble the perfect balance of movies that, given the low margins on ticket sales compared to the high return on concessions, would sell the most soft drinks at any given cinema.

Once perfected, organizations then preserve and defend their ‘sauce.’ I once helped a large hotel company embed an AI in the information system that set room rates for its one million rooms 90 days into the future. So valuable was that secret recipe that after investing well over $100 million in a joint venture with its travel partners, the company chose to walk away from the collective reservation system project rather than divulge the details of its yield management algorithm, an asset they called its ‘crown jewels.’

So how do successful organizations go about designing such jewels—the sauce that draws customers to their doors by the ‘billions and billions’ as McDonald’s now boasts? Is there a recipe for cooking up that kind of recipe?

For that, you’ll want to consider what my colleague Gerard F. McDonough ♼ Senior Managing Director of Ankura, discovered about the messaging most successful brands in the world use to attract customers. Gerry taught me early in my consulting career that every organization, intentionally or subconsciously, develops, safeguards, and works diligently to maintain and improve its sauce by following the same formula of success. He called it their ‘MVP,’ or Massive Value Proposition. Unlike the 33 ingredients (count ’em!) of a Big Mac’s value proposition, Gerry’s recipe called for only four ingredients:

- Conspicuous Benefit: What will buyers say, think, or implicitly understand they will get in exchange for their money?—ideally, only one.

- Colossal Distinction: In what ways is their product or service unique from that of their competitors?—one or two max.

- Honest Reason to Trust: What evidence will buyers rely on to accept the stated claims about Benefit(s) and Distinction(s)?—a few memorable anecdotes, slathered in truth.

Gerry’s research consistently showed that organizations that possessed and preserved those three ingredients in their offerings were nearly always found at the top of their respective pyramids.

“Think about Apple. What do you imagine you’re getting when you buy an Apple product? What compels you to buy it? Research shows you buy their products because (1) you can articulate what they will do for you; (2) you implicitly know what sets them apart from the alternative; and (3) you trust either from experience or hearsay that they will deliver on those expectations.”

Gerry’s final ingredient is the cauldron that boils the first three must-haves into a cohesive message that persuades ahead of your choice and continues to reinforce it after the fact.

“Every single message Apple communicates , from Steve Jobs to his product developers, throughout the marketing department down to the entry level service tech on the other end of the phone, clearly and consistently delivers the first three ingredients.”

Since meeting Gerry, in every organization I enter, when it comes to deriving (or at least reminding) my team’s or client’s value proposition, I get out his recipe book and start cooking. Good for goose and gander, Gerry’s approach applies equally to both institutions and individuals. We might not think of ourselves as products or services. (Sounds a little transactional, doesn’t it?) But when our consumers hire, promote, or give us a plum project to lead—insert your own goal here—that is exactly how we are viewed by those in a position to choose our offerings. Just as we might select Apple over Samsung—or vice versa—those in a position to ‘buy’ our talent ask themselves the same questions about us that we do when buying a new phone.

- What do I get from this person?

- In what ways is she different from that person?

- What makes me think he will deliver?

And if Gerry is right, everything we say, write, or do creates or adds to the reputation of our MVP—the Massive Value Proposition others will evaluate when making decisions about our future.

We might, then, occasionally ask ourselves whether our resumes address Gerry’s first three questions. And if our resumes, why not our presentations? Our elevator pitches? The way we conduct ourselves whenever people are watching, and even when they’re not?

By the way, according to the fine print on 4,000 bottles of Big Mac sauce that once sold out in Australia in only 15 minutes, here is the ingredient list of McDonald’s Special Sauce:

Soybean Oil, Pickle Relish, Distilled Vinegar, Water, Egg Yolks, High Fructose Corn Syrup, Onion Powder, Mustard Seed, Salt, Spices, Propylene Glycol Alginate, Sodium Benzoate, Mustard Bran, Sugar, Garlic Powder, Vegetable Protein, Caramel Color, Extractives of Paprika, Soy Lecithin, Turmeric, Calcium Disodium EDTA .

What’s in your sauce?

***

What’s Your Name? (9 September 2023)

Just beyond a toddler, I was asked by a swimming instructor if I was ashamed of my name. Too young to understand the question but old enough to remember it six decades later, I have since been sensitive to the impact of the sound—”of the sound”—of a name. I had by then heard the children’s trick-rhyme “Shakespeare / Kick in the Rear.” But it would take until college to come across the Bard’s nominal contribution to my heritage.

Full fathom five thy father lies

William Shakeseare, The Tempest

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell.

Preferring the idea of “life knell” to its polar antipodes, I have made it my business to usher in the new instead of predicting the demise of its opposite. In either case, I think of my name not for what it might mean to others but for what it signals uniquely to me. Much like my ancestors’ thousand-thousand combinations of bone, wit, gut, flash, and outbreak, the name they eventually bestowed upon me at least flavors some of what I have made of their gifts.

There was Beatrice de Geneve who died in Geneva, Switzerland 700 years to the day ahead of my birth. Is that why, not knowing that fact until decades later, I moved to her namesake hometown when I was 19?

And Eleanor of Aquitaine. She married King Richard II of England to produce my great-great-times-a-million grandfather before Richard locked her up in a tower in Chamonix. Having last week celebrated my 45th anniversary with my wife Kari, whose only trip to Chamonix has been with me to see the Alps (and not stay over for life), I have so far not followed in that beloved ancestor’s footprints.

Eleanor’s father returned from the Crusades with songs and stories he spread all over France. Guillame IX D’Aquitaine is considered one of the first Troubadours. Is that why I love music and story-telling?

Lady Godiva, infamous for a fantastic falsehood—it turns out she performed her social activism fully clothed!—is less known for the far more important stand she took against her cruel husband on behalf of his hapless renters. Have I been so bold in the causes I believe in?

All of us inherit an endless parade of ancestral traits known by any number of names. Exponential explosions are such that we need go back only seven generations—a mere century and a half—to amass 127 surnames. And that’s just on our mother’s side. From which of our progenitors have we received which traits, tendencies, and gifts?

Geneticists tell us it is theoretically possible that each of us possesses remnants of the genes of our ancestors from time immemorial. But randomness and the fact that for every generation, at least half of each parent’s DNA is left on the cutting room floor conspire to monkey with the probability of an exhaustive inheritance. Most genes seep from our ancestral pool, while proclivities, talents, preferences, and traits—especially paternal names—can persist over time. While we might not inherit our physicality from our combined 254 “recent” ancestors equally, we do tend to pick up things from our parents and grandparents, whom we might have come to know along the way.

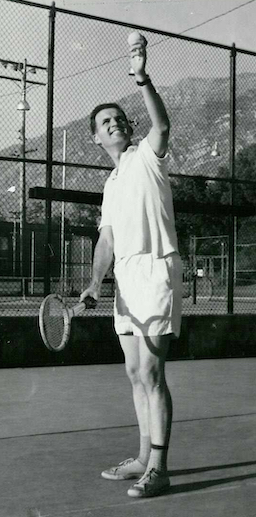

Yesterday, watching Carlos Alcaraz and Novak Djokovic, two dark-haired world number one and two tennis players, compete in semifinal matches at the U.S. Open tennis championships, texting my brother Abe throughout, reminded me that our dark-haired father qualified to play in that same tournament 75 years ago. And while I inherited from Dad my love of that wonderful sport, I’m sure I haven’t a fleck of his tennis DNA in my body. I do ponder some of his other gifts. In addition to athlete, he went by a host of names in his 80-year life—painter, architect, city planner, dreamer—not to mention husband, father, grandfather, and great-grandfather. His surname, then, changed only two generations earlier by a man whose father changed his own name a generation before that, is not the only name he passed along. Nor was my mother’s surname—Cloward—sandwiched between my first and last all she bequeathed to me. She went by singer, actor, beauty queen, radio host, and teacher. (Care to guess which of those five names I never got round to wearing?) Other names my parents passed along from their parents and grandparents include cobbler, pole vaulter, Pinkerton detective, pony express rider, and frontier settler, to name but a handful among dozens that have passed me right by as well (although I did learn to ride as a kid and managed to jump over my head before reaching my full height). Believing as I happen to that unlike DNA, trait secrets can persist across generations, I’m personally holding out for Grandpa Guillaume to whisper in my direction some of his classic storytelling chops.

When I think of all 254 surnames (256 if you count the two that were changed)—thanks mainly to siblings, whose diligence they inherited from our pioneer forbears and modern tools like FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com—I now know something about my eclectic name pool. I expect that within and across it, random and recessive genes notwithstanding, you and I each have unique access to a pool of thousands of traits, ticks, gifts, and carefully honed skills to call upon when drawing strength and solidarity from all our folk.

What are your names?

***

What’s Your Line? (4 September 2023)

For those who remember their dreams, do you ever get reruns? Mine are terrifying, like driving a car straight up a mountain so steep the wheels disengage from the sheer rock and I begin to drift back into space. Even scarier is frantically rummaging backstage for a script just minutes before I make my big entrance after not having bothered to learn my lines.

Some dreams imitate life. I learned to drive an automatic In the Rocky Mountains and a stick in the Swiss Alps. But in my experience, life can also imitate dreams though usually with a twist. On a real stage, if an actress forgets her lines, a script assistant scrupulously following every word will immediately come to her rescue.

Marian: You’ll find it in Balzac.

—Meredith Wilson, The Music Man

Mrs. Paroo: {Line?}

{Script Assistant: “Excuse me—”}

Mrs. Paroo: Excuse me for living but I never read it.

A few Broadway seasons ago, I enjoyed watching Hugh Jackman and Sutton Foster review the roles of Harold Hill and Marion Paroo in the first musical I ever saw as a kid, Meredith Wilson’s The Music Man. In its iconic opening sequence, a train car of traveling salesmen back-and-forths a collective diatribe on the state of their profession to the pre-rap rhythm of a locomotive chugging across the American Midwest of 1912.

Ya can talk, ya can talk, ya can bicker, ya can talk, ya can bicker, bicker, bicker, ya can talk, ya can talk, ya can talk, talk, talk, talk, bicker, bicker, bicker, ya can talk all ya wanna, but it’s different then it was. No it ain’t, no it ain’t, but ya gotta know the territory.

When their syncopated banter turns to the prospect of a newcomer to their territory, speculation rhythmically turns to gossip.

What’s the fellow’s line?

Never worries ‘bout his line.

Never worries ‘bout his line.

Or a doggone thing. He’s just a bang beat, bell ringing, Big haul, great go, neck or nothin’, rip roarin’, every time a bull’s eye salesman.

Turns out the fellow, one Professor Harold Hill, does have a line, and these days it’s selling musical instruments and band uniforms to gullible children and their parents.

He’s a music man

He’s a what?

He’s a what?

He’s a music man and he sells clarinets to the kids in the town

In those days, if a person was asked her line’, it might mean one of three things.

- “What’s your line of work?”

- “What’s your product line?”

- “What’s your elevator pitch, your opening line?”

There are times, of course when a person’s line can mean much more. For Harold Hill, his entire life boils down to a single hopeful, heart-breaking lament in the play’s deciding moment. The mayor has seen through his con; an angry anvil salesman is hot on his heels; and a crest-fallen boy who worships the ground Hill walks on now believes him to be a complete phony.

Hill: I always think there’s a band, kid.

In a life filled with hundreds of them, It’s Hill’s first truly genuine line.

My love for the theatre can spill over into my change work. With some clients, and not just those in Hollywood, I use scripts to steer an organization towards a common job ‘performance’. Instead of functional roles being defined in silos, it’s critical that every member of the team understands how their role ties to the vision and outcomes of the larger organization. To drive home this point, I encourage staff to write their own ‘lines,’ so to speak. They do this in the first person, as if on stage before the entire organization and its customers.

This can be a formal exercise:

Hotel Software Engineer: I write the code that optimizes our yield when setting room rates 90 days out so that the customer gets their best value and we our best price for their stay.

Or off the cuff:

Television Editor: I sit here reading the newspaper like it was the fire department, waiting to slide down my pole when the bell rings because nobody can predict when I’ll be called in for a last minute snip. I’m overpaid for the Sturm und Drang becuase the studio can’t get hold of a stringer to do it in a pinch.

Do I have a line? I do. Several in fact.

Here’s my line when I’m at home:

Scott: I am a happy husband, father, and grandfather in a kingdom of souls in number as the hours in a day, during which I love, worry, and rejoice over each of them.

And when I’m at work.

Scott: I am an American innovator, changesayer, and community developer hovering the middle distance between being and becoming.

Just as we wear several hats in life, we learn and say many lines along the way: lines to get us up in the morning; lines that move us to write that best-seller: lines that drive us to the treadmill, finish that report, design that product—um—line.

What are some of your lines? Are they written down? Have you memorized them by heart? Do you ever find yourself on your stage without them? Is there someone close you could whisper an aside for help who wouldn’t miss a beat?

You: Line?

Safely prompted, your own Sturm und Drang subsides into tranquil confidence. You know once more who you truly are.

***

What’s Your Box? (25 August, 2023)

When leading the transformation of a Hollywood studio, I began as I was trained: to listen first and ask questions later. What I came to understand was that professionals in the motion picture and television industry usually operated out of one—and only one—of three boxes.

- The Discovery Box. Every movie, TV show, and news program begins with a concept. Whether from a lone dreamer, a think tank, or a studio board—I was once even asked to query an AI for film ideas—in Hollywood, concept is king.

- The Delivery Box. Concepts are a dime a dozen if they cannot be developed into tangible, marketable, watchable programming.

- The Disintegration Box. Once ready for prime time, for their revenue streams to persist delivered programming must be kept from disintegrating—sliced and diced, repackaged, and where profitable, recycled, “sequelized,” or serialized.

The Boxes were not functional. There could be found, for example, finance and marketing types in every Box. But inside their local context, they formed part of a higher level of abstraction from which to view what was fundamentally happening across the enterprise from concept to cancellation.

The Hollywood Three-Box Model seemed to me an organic one, even Darwinian; the winningest concepts survive through Discovery and Delivery, and are kept alive ad infitium well into Disintegration.

What was not initially apparent was how products met up with functional professionals in each Box through which they flowed. Through evolution, selective hiring, deliberate culling, good fortune, or poor decision-making, the human makeup of each Box constantly self-corrected to optimize the Discover-Delivery-Disintegration cycle.

If you were comfortable—facile, productive, prolific—working in, say, the Delivery Box, the forces that maintained the integrity of that Box—creative, market-driven, economic, political, whatever—put and kept you in your “ideal” Box. Likewise, if you found yourself in the Disintegration Box but weren’t naturally suited to it —too creative, slow-to-crank, short on detail—you’d eventually be bounced out.

The Hollywood Model as we came to call the three-box structure applied to engineering a movie studio might not apply to your industry. In the tight community that is Hollywood, independent professionals come together on demand to construct an instant Delivery Box in response to an open call to action. When a new event is announced, networks of trusted professionals appear “out of nowhere” to deliver the product. After the event is “in the can,” the same network vanishes to reassemble around a new event elsewhere. The Boxes in your industry may be more stable. There might also be more or less than three, keeping in mind that efficient industry work flows tend not to require too many.

However your industry has evolved structurally, it might be useful to step back and periodically squint at the “Boxes” that may be shaping it. These are not obvious structures or processes that can be manipulated with moderate effort. They involve institutional boundaries dictated by the larger problem your industry—not just your organization—is trying to solve.

Which brings me to your Box. Once you’ve identified where you fit in your organization—again, I’m not talking about an office, a department, or even a proper function. I’m figuratively pointing out a higher level construct that makes your organization successful at what it does. Like the Hollywood studio, it probably won’t come with a proper name on an org chart. But if you take a look around, maybe squint a little, you’ll see your Box well enough. And If you find you are not comfortable in it, consider that it might be easier—and wiser—to retool yourself rather than the Box. Or, as the saying goes, you might even “think outside” it and jump Boxes altogether.

***

What’s Your Point? (August 21, 2023)

At 8:03 eastern yesterday morning, my smartphone notified me that Spain and England were down to their final minute in what had to have been a nail-biting one-nil Women’s World Cup final. By the time I clicked into the details, Spain had won its first-ever title. (A big shout-out to my friend, Nacho Fresco!)

Fortunately for the other guys, my professional football career (we called it soccer then) was cut short in elementary school when in the first and last playground game I ever suffered through, a ginormous third grader kicked wide of the bouncy pink and blue ball and cracked instead the metatarsal bone of my right foot.

My sport turned out to be tennis, a game where, unlike soccer, it’s not how many goals you score — in the longest Wimbledon match ever played, Nicolas Mahut scored 502 points to Mark Isner’s 478 but still lost three sets to two — but which points you win.

( In this summer’s run-up to the World Cup, I came across an astonishing football score. On October 31, 2002, in Tomasina, Madagascar, AS Adema bested L’Emyrne by a whopping 149 to nil. The most amazing thing about that match was not its margin of victory, but that every one of AS Adema’s 149 goals was kicked into their opponent’s net BY THEIR OPPONENT! )

What’s MY point?

Not long ago, trapped in an endless face-to-face goal-setting meeting going nowhere slow, I asked no one in particular where the meeting was heading.

“I mean, we’ve been at it for three hours, and I don’t see a single goal on the board.”

“What are you talking about, Scott? Look at all the points we’ve captured! There must be over a hundred!”

“My point exactly.”